You are here: Urology Textbook > Surgery (procedures) > Percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: Surgical Steps and Complications

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is an endoscopic minimally invasive procedure for the removal of kidney stones 1 cm in size or larger (Knoll et al., 2017). The abbreviations are PCNL or PNL. The synonym is percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy.

Indications

- Renal pelvic and calyceal stones over 1.5 cm in size

- Lower calyceal stones over 10 mm in size

- Renal calyceal stones with calyceal neck stenosis

- Renal stones refractory to treatment with ESWL or URS.

- With increasing miniaturization (mini-PNL), the morbidity of PNL could be reduced and the indication is expanded at the expense of ESWL or flex URS [see table treatment options for nephrolithiasis].

Contraindications of Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

- Untreated urinary tract infections

- Bleeding disorders

- Non-functioning kidney (less than 10% of GFR)

- Pregnancy

- Potential malignant tumor of the upper urinary tract or renal cell carcinoma.

Surgical Technique (Step by Step) of Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

Preoperative patient preparation:

Treat or exclude urinary tract infection before surgery, and perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is additionally recommended. General anesthesia is the standard anesthetic procedure, but spinal anesthesia is also possible for simple and presumably short procedures.

Insertion of a ureteral catheter:

Retrograde pyelography and insertion of a ureteral catheter (ideally with a balloon to seal the ureter) is done in the lithotomy position. The ureteral catheter has several advantages: dilation of the pyelocalyceal system to simplify percutaneous access, contrast for orientation, and preventing stone fragment migration into the ureter. A DJ ureteral stent enables retrograde filling via the bladder, which is also an option. Simple cases may be done without a ureteral stent.

Patient positioning for PNL:

Standard is prone positioning of the patient with slight flexion of the lumbar spine by an abdominal cushion. Advantages are better fixation of the kidney, reduced risk of bowel injury, and easy access to all calyceal groups.

PNL can also be done in a modified supine position (with or without elevation of the operated side with wedge support). Advantages include better tolerability of anesthesia, especially in obese or cardiopulmonary pre-diseased patients, and the possibility of simultaneous retrograde-antegrade stone therapy.

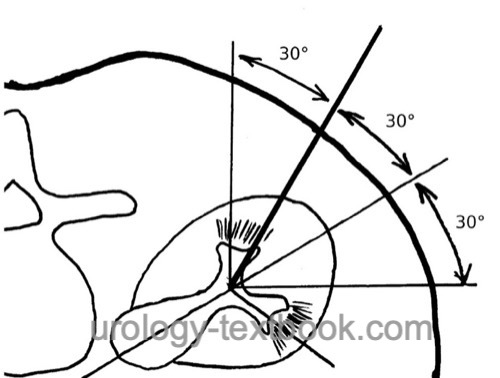

Percutaneous access:

After the puncture of a renal calyx, a rigid guide wire (Lunderquist wire) is advanced into the renal pelvis (Seldinger technique). Guidance of the initial puncture is possible either by ultrasound imaging or fluoroscopy in two planes. The most straightforward location is the dorsal inferior calyx. Depending on the stone location, a middle or superior calyx group puncture may also be necessary.

|

Dilatation of the working channel:

Several dilation techniques are possible to create a working channel for nephrolithotomy.

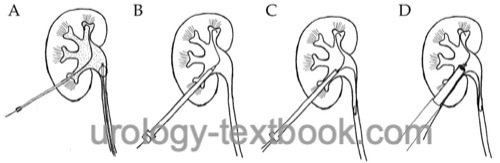

Usage of a second safety wire:

A dilator with a sheath is advanced along the guide wire into the renal pelvis. The dilator is removed, and an additional safety wire is inserted via the sheath. The safety wire allows re-entry into the pyelocalyceal system after possible dislocation of the working channel. The rigid Lunderquist guide wire is used for further dilatation of the working channel.

Single-Step dilatation:

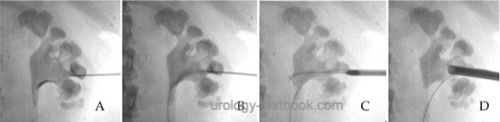

Dilatation and insertion of a working channel is possible in one step (Mini-PNL 14–21 CH, thin Amplatz sheaths up to 24 CH). The rigid guide wire is removed after the working channel is safely positioned in the pyelocalyceal system (check with nephroscopy) [fig. \ref{pnl_roentgen}].

|

Sequential dilatation:

Sequential dilatation with a metal telescopic dilatation set or balloon dilators enables the placement of thick working channels (Nephroscope or Amplatz sheaths up to 30 CH). After safe positioning of the working channel in the pyelocalyceal system (check with nephroscopy), the rigid guide wire is removed.

|

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Stone extraction without disintegration:

Stone extraction without disintegration is only an option for small stones, as dilatation of the nephrostomy tract is necessary to the diameter of the stone. Renal trauma and the risk of bleeding increase exponentially with the diameter of the working channel.

Stone disintegration:

The method of choice is laser lithotripsy (holmium, thulium). Small stone fragments are removed with the irrigation current. Larger fragments can be removed with forceps or the irrigation current and retraction of the nephroscope (suction effect). Older techniques of stone fragmentation include ultrasonic lithotripsy, a pneumatic hammer (lithoclast), or electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL).

Multitract PNL:

The advancement of nephroscopes and instruments allows PNL with 15–20 CH working channels. The lower trauma to the kidney enables the treatment of complex staghorn stones with multiple simultaneous working channels to different calyceal groups.

Nephrostomy tube:

A postoperative nephrostomy ensures urinary flow and compresses bleeding from the working channel. Patients with significant bleeding need a nephrostomy with the same diameter as the working channel, and the balloon of the nephrostomy can be used to compress the working channel further. Without bleeding, a thinner nephrostomy is sufficient, which causes less pain.

Tubeless PNL:

Omitting the nephrostomy tube after PNL with (tubeless) or without DJ ureteral stent (totally tubeless) is safe and associated with less patient discomfort (Tirtayasa et al., 2017). Tubeless PNL is a good option in selected patients after uncomplicated PNL (with single access tract, minimal intraoperative bleeding, without perforation of the collecting system, without infect stones and without the need for second look nephroscopy).

Postoperative Care

General Measures:

Early mobilization, thrombosis prophylaxis, laboratory tests (hemoglobin, creatinine level), regular physical examination of the abdomen.

Analgesics:

With a combination of NSAIDs and opioids.

Drains and Catheters:

Early removal of the bladder catheter is possible within one day after uneventful surgery. The nephrostomy catheter is removed after 1–3 days, and antegrade pyelography via the nephrostomy can be used to check the treatment success and the passage of urine into the urinary bladder.

Complications of Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

Bleeding:

Postoperative venous bleeding can be stopped by passager clamping of the nephrostomy. Bleeding requiring transfusion is necessary for 1–3%, depending on expertise and the diameter of the working channel (Wollin et al., 2018). Rarely, radiological embolization, revision by open surgery, and possibly nephrectomy are necessary because of bleeding. Delayed bleeding indicates the formation of an arteriovenous fistula or pseudoaneurysm.

Infection:

Fever (10%), urosepsis (0,5%).

Injury of the collecting system:

Perforation (up to 7%), fluid extravasation with possible TUR syndrome, ureteral injury, strictures (<1%).

Injury of neighboring organs:

Pneumothorax or hydrothorax (1–4%), increased with supracostal access. Injury of colon, duodenum, liver, and spleen (<1%).

| Urologic Surgery | Index | Abbreviations |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Kim u.a. 2003 KIM, S. C. ; KUO, R. L. ;

LINGEMAN, J. E.:

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy: an update.

In: Curr Opin Urol

13 (2003), Nr. 3, S. 235–41

Knoll T, Daels F, Desai J, Hoznek A, Knudsen B, Montanari E, Scoffone C, Skolarikos A, Tozawa K. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy: technique. World J Urol. 2017 Sep;35(9):1361-1368. doi: 10.1007/s00345-017-2001-0.

Lahme u.a. 2001 LAHME, S. ; BICHLER, K. H. ;

STROHMAIER, W. L. ; GOTZ, T.:

Minimally invasive PCNL in patients with renal pelvic and calyceal

stones.

In: Eur Urol

40 (2001), Nr. 6, S. 619–24

P. M. W. Tirtayasa, P. Yuri, P. Birowo, and N. Rasyid, “Safety of tubeless or totally tubeless drainage and nephrostomy tube as a drainage following percutaneous nephrolithotomy: A comprehensive review.,” Asian J Surg., vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 419–423, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2016.03.003.

Wollin DA, Preminger GM. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy: complications and how to deal with them. Urolithiasis. 2018 Feb;46(1):87-97. doi: 10.1007/s00240-017-1022-x.

Deutsche Version: Technik und Komplikationen der perkutanen Nephrolithotomie

Deutsche Version: Technik und Komplikationen der perkutanen Nephrolithotomie

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.