You are here: Urology Textbook > Kidneys > Nephrolithiasis

Nephrolithiasis: Epidemiology and Etiology

- Nephrolithiasis: Etiology and Epidemiology

- Diagnosis of Nephrolithiasis and Renal Colic

- Treatment of Kidney and Ureteral Stones

Definition

Nephrolithiasis is the calculi formation in the renal pelvic calyx system, which can migrate into the urinary tract (urolithiasis). EAU guidelines: Urolithiasis. Nephrolithiasis has to be separated from lower urinary tract calculi, which primarily arise in the bladder, see section bladder stones.

|

Epidemiology of Nephrolithiasis

Diseases of affluence:

There is an increased risk of nephrolithiasis in adults in societies without food shortages and with reduced physical activity (risk factor: metabolic syndrome). In these societies, however, the risk of urolithiasis in children is reduced.

Risk of disease:

The incidence of nephrolithiasis is approximately 0.5% in Europe and the USA (500/100.000 persons per year). The lifelong risk for nephrolithiasis is 10–15%. After the first episode, the recurrence risk is 50% within ten years (Moe et al., 2006). 10–20% experience three or more recurrences during their life. Men:women = 4:1, familial increased risk.

Etiology and Pathogenesis of Nephrolithiasis

Pathogenesis

Matrix:

Stone crystals are deposited secondarily on an organic matrix to form calculi. The matrix has a share of 2–10% of the stone.

Crystallization:

Five mechanisms lead to the formation of stones:

- Oversaturation

- Nucleation

- Crystalline growth

- Aggregation of crystals

- The shortage of nucleation, crystallization, and aggregation inhibitors supports the formation of stones: pyrophosphate, citrate, magnesium, glycosaminoglycans, heparin, and chondroitin sulfate.

Calcium Stones

Hypercalciuria is defined variably: 5–7.5 mmol (200–250 mg) calcium/24 h urine. Hypercalciuria is found in 50% of stone patients. 80% of urinary stones are calcified. 50% of the blood calcium (almost 100% of the ionized calcium) is filtered into the primary urine, 95% is absorbed in the proximal and distal tubules, and less than 2% is excreted.

Chemistry:

Calcium-containing stones are:

- weddellite stones (calcium oxalate dihydrate)

- whewellite stones (calcium oxalate monohydrate)

- hydroxyapatite stones (calcium phosphate)

- brushite stones (calcium hydrogen phosphate)

Absorptive hypercalciuria:

The regular food intake contains 500–1000 mg of calcium; typically, 150–200 mg are absorbed in the small intestine and later excreted via the urine. With increased calcium absorption in the small intestine, the calcium concentration in the blood increases, which leads to a reduced parathyroid hormone concentration. The reduced parathyroid hormone level leads to reduced tubular calcium absorption and, thus, to hypercalciuria.

Resorptive (hormonal) hypercalciuria:

Primary hyperparathyroidism leads to hypercalcemia due to increased calcium resorption from the bone and absorption from the intestine: hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, and recurrent nephrolithiasis develop.

Renal hypercalciuria:

Unclear tubular defects in calcium reabsorption result in hypercalciuria and hypocalcemia. Hypocalcemia leads to increased release of parathyroid hormone (secondary hyperparathyroidism), increased synthesis of vitamin D3, mobilization of calcium from the bone, and increased absorption from the intestine.

Monogenetic causes of hypercalciuria:

See table Genetic causes of hypercalciuria.

. .Hyperuricosuria:

Hyperuricosuria leads to the formation of uric acid stones (see below) and increases the risk for calcium stones. Hyperuricosuria reduces the efficiency of inhibitors of lithogenesis, and typically calcium oxalate stones are formed.

Hyperoxaluria:

Increased urinary oxalate excretion (>0.5 mmol/24 h urine) leads to calcium oxalate stones.

Secondary hyperoxaluria:

Increased enteral oxalate absorption arises from chronic diarrheal states or steatorrhea, such as in ileum or pancreatic diseases. The fats in the intestine consume the calcium in the intestine during saponification processes, which normally binds the oxalate and prevents absorption. Other causes are dietary factors such as foods rich in oxalate (spinach, rhubarb, chard) or vitamin C supplements.

Primary hyperoxaluria:

Due to enzyme defects in the liver, there is a massive increase in oxalic acid, which is deposited in various tissues. Oxaluria is typically over 1 mmol/24 h urine. Depending on the genetic defect, the disease can lead to end-stage renal failure. In addition to urinary stone metaphylaxis (see the section treatment of kidney stones), combined liver-kidney transplantation is accepted for treatment in severe cases.

Hypocitraturia:

Citrate is an inhibitor of lithogenesis by complexing with calcium and hindering calcium salt crystallization. Hypocitraturia is found in 20–60% of the calcium stone carriers alone or in combination with other metabolic disorders as the cause of the stone formation.

The reduced excretion of citrate arises due to an increased acid load on the body: distal renal tubular acidosis (see below), hypokalemia, chronic diarrhea, hypomagnesemia, fasting, excessive meat consumption, androgen abuse and excessive physical training (bodybuilder stones). The bacteria in urinary tract infections can also consume citrate.

Low urine pH:

A low urine pH is a risk factor for the formation of calcium stones. There are several mechanisms for continuously acidic urine pH values below 6 (acidic arrest), which is associated with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a high animal protein intake.

Renal tubular acidosis (RTA):

Renal tubular acidosis is a group of tubular disorders of proton excretion or bicarbonate absorption with the formation of metabolic acidosis.

Type 1 (distal) RTA:

Type 1 RTA is a disturbed proton secretion of the distal nephron (defect in type A intercalated cells of the collecting tubes) with the development of hypokalemic, hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and increased urine pH. Distal RTA is a heterogeneous disorder with different mutations, enzyme defects, and phenotypes. Typically, the daily profile of the urine pH always shows values above 5.8, and calcium phosphate stones are formed. Even after exposure to acid (ammonium chloride 0.1 g/kgBW), the urine pH remains above 5.4. Depending on the level of metabolic acidosis, a distinction is made between incomplete (normal bicarbonate concentration in the BGA) or complete (reduced bicarbonate concentration) renal tubular acidosis.

Type 2 (proximal) RTA:

A defect of bicarbonate absorption in the proximal tubule leads to growth retardation in children, hypokalemia, metabolic acidosis, and metabolic bone disease. Citrate excretion is relatively normal, and nephrolithiasis is uncommon.

Type 4 (distal) RTA:

Type 4 RTA is caused by chronic kidney disease (e.g., interstitial nephritis, diabetic nephropathy) with reduced sodium reabsorption and insufficient proton and potassium excretion. In addition, there is resistance to aldosterone. Nephrolithiasis is not typical.

Other Types of Nephrolithiasis

Infection stones:

Infection stones (10% of all kidney stones) consist of magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate (MAP, struvite) but may also contain calcium phosphate. Urinary tract infections with urea-splitting bacteria (enzyme urease) cause ammonium production and alkaline urine (>7), which causes MAP crystals to precipitate. The most common urease-producing bacteria in urinary tract infections are Proteus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and Staphylococci. Infections stones are often large (staghorn calculi), especially if several clinical risk factors are present: urinary malformations, diabetes, neurologic disorders, immobility, spinal cord injury, and indwelling catheters.

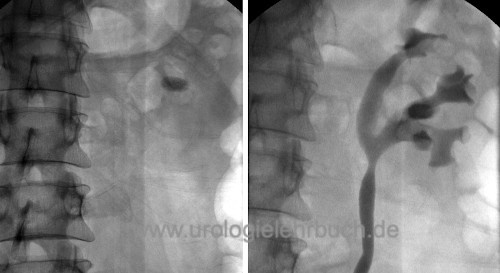

Uric acid stones:

Uric acid stones (10% of all urinary stones) are X-ray negative (not visible in conventional X-ray abdomen) but create the typical acoustic shadow in ultrasound and are visible in computer tomography. Uric acid stones form in hyperuricosuria, and with an acidic urine pH (below 6). A low diuresis is also a risk factor.

Hyperuricosuria:

Hyperuricosuria is a daily uric acid excretion over 4 mmol/24-hour urine collection; hyperuricemia is not always present. Hyperuricosuria is caused by increased purine intake with food, endogenous overproduction due to enzyme defects, myeloproliferative diseases, tumor lysis syndrome, chemotherapy, medication (probenecid), or catabolic situations.

Cystine stones:

1–2% of all urinary stones. Heterozygous (1:200) and homozygous (1:20,000) manifestation of cystinuria (>0.8 mmol/24 h urine) leads to the precipitation of cystine stones at acidic pH. X-ray imaging typically shows a rounded, frosted glass-like stone. Cystine stones are unsuitable for therapy with ESWL.

Xanthine stones:

Xanthine stones arise from the congenital defect of xanthine oxidase. They are not radiopaque, like uric acid stones.

2,8-Dihydroxyadenine stones:

Children with congenital defects of the adenine phosphoribosyl transferase (APRT) form 2,8-dihydroxyadenine stones.

Indinavir stones:

Medication with the HIV virostatic drug indinavir may lead to kidney stones, which are not radiopaque and are not reliably recognized even in CT.

| Kidney transplantation | Index | Renal colic |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Coe u.a. 2005 COE, F. L. ; EVAN, A. ;

WORCESTER, E.:

Kidney stone disease.

In: J Clin Invest

115 (2005), Nr. 10, S. 2598–608

EAU guidelines: Urolithiasis

Moe 2006 MOE, O. W.:

Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management.

In: Lancet

367 (2006), Nr. 9507, S. 333–44

Deutsche Version: Epidemiologie und Ursachen der Nephrolithiasis

Deutsche Version: Epidemiologie und Ursachen der Nephrolithiasis

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.