You are here: Urology Textbook > Kidneys > Chronic kidney disease

Chronic Kidney Disease: Etiology, Symptoms, and Treatment

Definition of Chronic Kidney Disease

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined as abnormalities of kidney structure or function, present for >3 months, with implications for health and CKD is classified based on cause, GFR category, and albuminuria category (KDIGO2012):

- Abnormal kidney function: glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min (standardized to a body surface area of 1,73m2)

- Markers of abnormal kidney structure: albuminuria or proteinuria, chronic changes in urine sediment, tubular disorders, histologically proven kidney diseases, abnormal kidney structure in imaging methods, history of kidney transplantation.

GFR categories in CKD:

The reduction in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in CDK is classified into six stages:

Albuminuria categories in CKD:

Albuminuria is classified into three stages A1–A3, it is used for further risk assessment of CKD, see table CNI risk assessment:

Prognosis and risk assessment:

The GFR and albuminuria categories reflect the prognosis and risk of progression of CKD, see table CNI risk assessment:

| Category | A1 | A2 | A3 | Prevalence |

| G1 | 55.6% | 1.9% | 0.4% | 58% |

| G2 | 33% | 2.2% | 0.3% | 35% |

| G3a | 3.6% | 0.8% | 0.2% | 4.6% |

| G3a | 1% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 1.6% |

| G4 | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.4% |

| G5 | 0% | 0% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Prevalence | 93.2% | 5.4% | 1.3% |

Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease

Prevalence of CKD

See table CNI risk assessment for the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the USA.

Prevalence of end-stage renal failure:

Europe 92 per 100,000, USA 208 per 100,000. Prevalence is increasing due to better treatment outcome. See also table CNI risk assessment for the prevalence in the USA.

Incidence of end-stage renal failure:

Europe 13 per 100,000, USA 35 per 100,000 (Heaf et al., 2017). Incidence is decreasing due to better treatment of the early stages of CKD.

Etiology: Causes of CKD

The most common causes of end-stage renal failure in the United States (2008) were diabetic nephropathy (44%), vascular-related end-stage renal failure (peripheral artery disease, arterial hypertension) in 27%, glomerulopathy (7%), polycystic kidney disease (3%), unknown or mixed causes (19%).

Prerenal causes:

Hypovolemia, sepsis, shock, renal artery stenosis, hepatorenal syndrome, congestive heart failure (cardiorenal syndrome).

Glomerulonephritis:

Primary or secondary forms.

Interstitial nephritis:

Nephrolithiasis, hydronephrosis, vesicoureteral reflux, gout, nephrocalcinosis, drug-induced (allergic) nephritis, analgesic nephropathy, Balkan endemic nephropathy caused by aristolochic acid.

Cystic kidney diseases:

Tuberous sclerosis, ADPKD, ARPDK, medullary sponge kidney, juvenile nephronophthisis, medullary cystic kidney disease, congenital nephrotic syndrome.

Systemic diseases:

Diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, autoimmune diseases with vasculitis (Goodpasture syndrome, Wegener's granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, SLE, Schönlein-Henoch purpura, thrombotic-thrombocytopenic purpura), amyloidosis.

Microangiopathies:

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome, DIC, malignant hypertension, antiphospholipid antibodies.

Postrenal causes:

Subvesical obstruction (urethral valves, BPH), vesicoureteral reflux, Prune-Belly syndrome, ureteral stones. See also section BPH.

|

Pathophysiology

Glomerular adaptation to reduced renal function:

The remaining nephrons hypertrophy and increase the GFR. After nephrectomy, the postoperative GFR increases from 50% to 80% of the baseline function within a few months.

Mechanisms of the GFR increase are hypertrophy of the glomerulus with increased glomerular blood flow, increased glomerular filtration pressure, and increased filtration area.

Glomerulotubular Balance:

The functional state of the tubules is a mirror of the glomerular function. A hypertrophied glomerulus induces a hypertrophied tubule, while an atrophic glomerulus induces an atrophic and obliterated tubule.Intact nephron theory:

Progressive CKD is usually the progressive loss of nephrons; the remaining nephrons are hypertrophied and must work harder than a single nephron in a healthy kidney.

Above a certain workload, chronic damage to these remaining nephrons arises because the regeneration capacities are exceeded, leading to the progression of CKD and end-stage renal failure. The histological sign of chronic nephron damage is glomerulosclerosis, which causes proteinuria.

Failure of the excretion function:

Reduced urine excretion leads to metabolites and foreign substances (medications) accumulation. The higher concentration of the substances in the primary urine compensates for the lower kidney performance and enables a comparable excretion (stage of compensated retention).

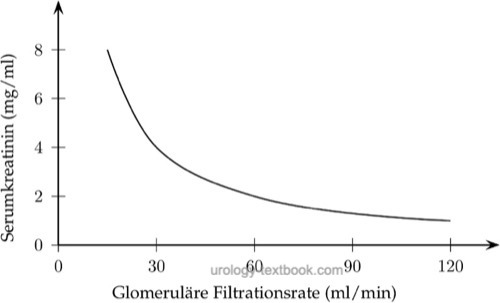

Substances with exclusively glomerular filtration (without tubular secretion or absorption), such as creatinine, have plasma concentrations directly dependent on the GFR. Halving the GFR doubles the serum concentration. A reduction of GFR by 75% leads to a significant (fourfold) change in plasma concentration. However, further even slight reductions in the GFR now lead to dramatic changes in the creatinine concentration:

|

Substances with additional tubular absorption or secretion (e.g., phosphate, urate and potassium) can have normal plasma concentrations with severely decreased GFR, because tubular mechanisms (reduced reabsorption or increased secretion) compensate the reduced filtration. Natrium and water have normal concentrations even in end-stage renal failure due to due to pronounced compensation mechanisms.

Electrolyte disturbances:

A GFR above 5 ml/min is sufficient for a marginally compensated water and electrolyte balance. The osmolarity of the urine in a badly damaged kidney is close to the plasma (isosthenuria). The kidney cannot excrete concentrated or highly diluted urine.

Life-threatening hyperkalemia is not common in end-stage renal disease because the potassium secretion in the distal tubule is intact. Risk factors for the development of hyperkalemia are: acidosis, oliguria, sodium deficiency, potassium-sparing diuretics, hypoaldosteronism or increased potassium intake.

The reduced excretion of protons leads to the formation of metabolic acidosis.

Endocrine dysfunction in CKD:

- Renal anemia will develop due to decreased erythropoietin secretion.

- Renal osteodystrophy: The lack of renal hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D causes hypocalcemia and mineralization disorders in the bones. Secondary hyperparathyroidism (see below) contributes to osteopathy.

- Secondary hyperparathyroidism: the increasing phosphate concentration leads to hyperparathyroidism.

Uremic organ dysfunction:

Almost all organ systems are harmed by uremia, this affects the cardiovascular system in particular and explains the high mortality rate under dialysis. The toxins responsible for uremia originate primarily from protein metabolism; in addition to urea, guanidines, urates, creatinine, tryptophan, tyrosine, end products of nucleic metabolism, polyamines and phenols are to be mentioned.

In addition to the excretion function, the kidney also has an inactivating function for many endogenous messenger substances (including parathyroid hormone, glucagon, insulin, LH, prolactin). Inactivation is insufficient due to the reduced kidney function.

Molecular mechanisms of uremia:

The impaired function of the Na-K-ATPase leads to changes in the electromechanical properties, the resting membrane potential and the cell volume. Furthermore, the reduced activity of the Na-K-ATPase is the cause of hypothermia and a reduced basal metabolism.

Protein metabolism:

Uremia leads to protein and energy deficiency with a catabolic metabolic state. Weight loss is masked by the tendency to retain water and sodium.

Carbohydrate metabolism:

There is a slight glucose intolerance, which per se does not require therapy (azotemic pseudodiabetes). The causes are peripheral insulin resistance and activation of glucagon and catecholamines.

Lipid metabolism:

Hypertriglyceridemia and reduced HDL cholesterol lead to arteriosclerosis.

Kidneys:

Unclear cystogenic and mutagenic substances of uremia lead to acquired cystic kidney disease and renal cell carcinoma.

Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Kidney Disease

Signs of electrolyte disturbances:

Volume expansion, hyper- or hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia.

Hormone disorders:

Osteomalacia, glucose intolerance, impotence, decreased libido, amenorrhea and hypothermia.

Nervous system:

Fatigue, headache, memory disorders, muscle spasms, restless legs syndrome, peripheral neuropathy, paralysis, cramps and vigilance disorders.

Cardiovascular system:

Arterial hypertension, pulmonary edema, dyspnea, pericarditis, myocardial ischemia due to accelerated arteriosclerosis and cardiac arrhythmia.

Skin:

Pallor, hyperpigmentation, itching and bleeding.

Gastrointestinal tract:

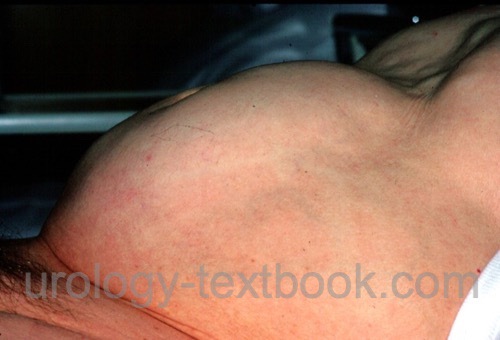

Weight loss, nausea and vomiting, uremic fetor, diarrhea, stress ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, ascites and peritonitis.

Renal symptoms:

Local complaints of cysts or kidney tumors are rare. Further complaints depend on the underlying renal disease.

Hematopoietic system:

Anemia (normocytic, normochromic), lymphocytopenia, bleeding tendency, immunodeficiency and splenomegaly.

Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease

Physical examination:

Arterial hypertension? Vascular status? Clinical signs of uremia?

Urine tests:

Urine sediment, urine culture. Measurement of albumin excretion: either 24-hours urine collection or albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) in early morning urine sample.

Laboratory tests:

Complete blood count, creatinine, urea, uric acid, cystatin C, natrium, potassium, calcium, phosphate, serum protein electrophoresis, blood gas analysis, liver enzymes, blood sugar and HbA1C.

Ultrasound imaging:

Renal ultrasound imaging (renal size? cysts? tumors?). bladder ultrasound imaging: (residual urine?), ascites?.

Kidney biopsy:

Is necessary in unexplained renal failure, nephritic or nephrotic syndrome.

Treatment of CKD: Prevent Disease Progression

Lifestyle:

Advise to quit smoking, weight control and weight loss if necessary, regular physical activity.

Protein intake:

A low-protein diet (0.8 g/kg/day) reduces the hyperfiltration of the remaining nephrons and is indicated below a GFR of 60 ml/min.

Arterial hypertension:

A reliable normalization of blood pressure reduces the progression of renal failure. The goal is a medium arterial pressure below 95 mmHg. ACE inhibitors and AT1 antagonists are particularly nephroprotective and drugs of first choice.

Lipid metabolism:

Aggressive dietary and medicinal reduction of LDL cholesterol is recommended to lower the excessive mortality due to cardiovascular diseases.

Inhibition of platelet aggregation:

Antiplatelet drugs are recommended to lower the excessive mortality of cardiovascular diseases, e.g., ASA 100 mg once daily.

Fluid intake:

Excess drinking does not slow the progress of CKD. With advanced CKD, the kidneys have no ability to balance fluid intake variations: weigh daily and if necessary balance urine volume and fluid loss. The goal is a diuresis of 2–2.5 l/d. The fluid intake should be 500 ml above the fluid loss. Edema is treated by loop diuretics and fluid/salt restriction.

Electrolyte intake:

Low-potassium and low-phosphate diet. In hyperkalemia, acute treatment is possible with intravenous sodium bicarbonate or glucose/insulin. For chronic hyperkalemia, oral therapy with resonium is possible.

Renal osteopathy:

The basis for avoiding secondary hyperparathyroidism is the low-phosphate diet and phosphate-binding oral medications (calcium and aluminum salts, sevelamer and lanthanum carbonate). The substitution of vitamin D3 is also important.

If hyperparathyroidism develops despite all efforts, the inhibition of parathyroid hormone release is possible with cinacalcet, a modulator of the calcium-sensitive receptor. Alternatively or as a last measure, the surgical removal of the parathyroid glands is necessary.

Renal anemia:

A hemoglobin concentration of at least 11 g/dl is preferable. Renal anemia is treated with erythropoietin, dosage e.g., 25–50 U/kgKG 3×/week. Regular checks of transferrin saturation and ferritin ensure a sufficient iron store, supplementation only if needed.

Treatment of CKD: Renal Replacement Therapy

Dialysis:

Indications to commence dialysis are: therapy-resistant hyperkalemia, acidosis, uremic symptoms, pericarditis or fluid overload. The level of GFR for symptomatic uremia is variable, see next section dialysis.

Renal transplantation:

See section kidney transplantation.

Prognosis

The prognosis of CKD is primarily determined by diseases of the cardiovascular system. The mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases is increased 2 to 10 times, depending on GFR and albuminuria stage.

| Acute renal failure treatment | Index | Dialysis |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Meguid El Nahas und Bello 2005 MEGUIDEL NAHAS, A. ; BELLO, A. K.:

Chronic kidney disease: the global challenge.

In: Lancet

365 (2005), Nr. 9456, S. 331–40

Ruggenenti u.a. 2001 RUGGENENTI, P. ; SCHIEPPATI, A. ; REMUZZI, G.:

Progression, remission, regression of chronic renal diseases.

In: Lancet

357 (2001), Nr. 9268, S. 1601–8

Deutsche Version: Chronische Niereninsuffizienz: Definition, Ursachen und Epidemiologie. und Chronische Niereninsuffizienz: Diagnose und Therapie.

Deutsche Version: Chronische Niereninsuffizienz: Definition, Ursachen und Epidemiologie. und Chronische Niereninsuffizienz: Diagnose und Therapie.

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.