You are here: Urology Textbook > Surgery (procedures) > Open partial nephrectomy

Open Partial Nephrectomy: Surgical Steps and Complications

Open partial nephrectomy is the standard technique for organ-sparing resection of renal tumors. The minimally invasive alternatives to open partial nephrectomy are (robotic-assisted) laparoscopic partial nephrectomy or retroperitoneoscopic partial nephrectomy. Review literature: (Novick et al., 2002).

|

Indications for Partial Nephrectomy

Imperative partial nephrectomy:

Partial nephrectomy should always be done (if technically possible) in patients with renal cell carcinoma in a solitary kidney, if bilateral tumors are present, in chronic kidney disease, or for patients with hereditary renal cell carcinoma.

Elective Indications:

If technically possible, a partial nephrectomy should be performed for every T1 tumor. Retrospective comparisons between nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy for T1 tumors showed a better prognosis for a partial nephrectomy due to the reduction of cardiovascular events (Zini et al., 2009) (Weight et al., 2010). If this reduction of cardiovascular events is due to better renal function or selection bias is unclear, the randomized EORTC study (nephrectomy vs. partial nephrectomy) did not demonstrate this effect (Van Poppel et al., 2011).

Partial nephrectomy for benign diseases:

- Calyceal diverticula

- Duplex kidney with a malfunctioning (upper) portion

- Hydatid cysts

Contraindications

Coagulation disorders. The other contraindications depend on the surgical risk due to the patient's comorbidity, the renal function of the contralateral kidney, and the surgical procedure's impact on the patient's life expectancy.

Surgical Technique of Partial Nephrectomy

Preoperative patient preparation:

- Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis.

- Perioperative bladder catheter and gastric tube.

- Consider epidural anesthesia.

- Consider the placement of a ureteral stent (DJ or MJ) for deep partial nephrectomy.

Surgical approach:

Most cases are managed using the retroperitoneal flank incision, but a transperitoneal ventral approach (subcostal incision or midline laparotomy) is also possible, depending on the tumor location. The first steps of the procedure are the identification and control of the ureter and renal vessels with vessel loops. Mobilize the kidney without removing the perinephric fat overlying the tumor.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Renal ischemia:

Resect small polar tumors without ischemia and limit bleeding with the assistant's manual compression of the renal parenchyma. Preparation under ischemia in a bloodless field is helpful for larger tumors. The tolerable warm ischemia time for the kidney is controversial, but it should not exceed 30 min. Several techniques are possible for ischemia: bulldog clamp, vessel loop (Rummel tourniquet), or Satinsky clamp to occlude the hilar vessels. Generally, the vein is not clamped since ischemic damage to the kidney should be lower with selective clamping of the renal artery. Cool the kidney after clamping for complex partial nephrectomy, and the tolerable (cold) ischemia time is significantly longer.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

An osmotic diuretic such as mannitol before (and after) clamping the renal vessels is often used to reduce reperfusion injury after renal ischemia. Mannitol's protective factors are its increase in diuresis and antioxidant properties. The dosage is usually 25 g. Despite the widespread use of mannitol in the context of partial nephrectomy, reliable studies supporting its use do not exist (Cosentino et al., 2012) (Power et al., 2012).

Tumor excision:

Various techniques are used depending on the location and size of the renal tumor: enucleation, wedge excision, and polar resection. In rare cases, extracorporeal partial nephrectomy with autotransplantation is done. The safety distance to the tumor has no prognostic significance (Minervini et al., 2012). The goal is to achieve a complete macroscopic resection; a frozen section examination offers no additional safety and is only recommended in doubtful cases with highlighting the suspicious area (Dagenais et al., 2018).

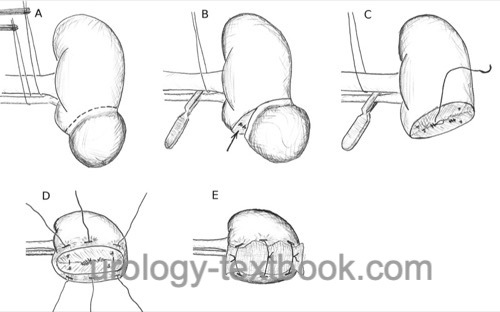

The resection of the tumor without ischemia is performed with the help of an electric scalpel or ultrasonic knife. If the resection is done under ischemia, sharp and blunt dissection without coagulation allows a perfect visualization of the layers. Visible vessels are sutured (figure-of-eight stitch) or closed with clips. If the collecting system is entered, it is closed with a running suture. Finish the preparation under ischemia within 20 minutes. After clamp removal, stop bleeding with selective suturing. Approximate the cortical edges with interrupted sutures and clips [fig. surgical technique of partial nephrectomy]. The interrupted sutures are tied over a bolster (e.g., resorbable cellulose or a flap of perinephric fat). Hemostyptic agents (Floseal, Tachosil, Surgiflo) can support hemostasis and simplify the operation.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Lymphadenectomy:

Lymphadenectomy is unnecessary for localized renal tumors without lymph node enlargement (T1–2 cN0) since the risk for lymph node metastases is very small, and lymphadenectomy did not show any survival advantage in a large EORTC study (Blom et al., 1999 and 2009). Nevertheless, enlarged lymph nodes should be removed with a limited regional lymphadenectomy.

Ureteral stenting and wound drainage:

Wound drainage is always wise. If the collecting system has been entered deeply, a DJ ureteral stent may be inserted via the opened collecting system or after suturing of the renal defect via a pyelotomy. In addition, a foley catheter is inserted for 5–10 days, depending on the daily volume of the drainage.

Postoperative Care after Partial Nephrectomy

General Measures:

- Early mobilization

- Respiratory therapy

- Thrombosis prophylaxis

- Laboratory tests (hemoglobin, creatinine)

- Regular physical examination of the abdomen and incision wound.

Analgesics:

Use a combination of NSAIDs and opioids. An epidural anesthesia facilitates postoperative pain management.

Diet advancement:

Remove the nasogastric tube after surgery and allow small sips of clear liquids. On postoperative day 1, allow yogurt or pudding. If the patient feels well, allow small amounts of solid food (appetite-driven) starting on postoperative day 2.

Drains and Catheters:

For stable patients without ureteral stents, early removal of the bladder catheter within 1–2 days is possible after uneventful surgery. Remove the wound drainage if the daily drainage is below 50 ml. Patients with ureteral stents need a bladder catheter until the removal of the wound drainage is possible.

Complications of Partial Nephrectomy

See table complications of radical and partial nephrectomy for complications after partial nephrectomy (in comparison to radical nephrectomy); the data is from randomized and retrospective studies. The risk for bleeding and postoperative interventions is higher after partial nephrectomy.

| Complication | Radical nephrectomy | Partial nephrectomy |

| Significant hemorrhage | 1,1 % | 3,4 % |

| Hemorrhage <0,5 l | 96 % | 87 % |

| Urinoma | 0 % | 4 % |

| Reintervention | 2,4 % | 4,4 % |

| Mortality | 2 % | 1,6 % |

Bleeding risk:

The risk of blood loss over 500 ml is around 13%. In the case of postoperative bleeding, radiological embolization is the best option. However, postoperative bleeding can rarely enforce surgical revision, which may end with a nephrectomy. A rare cause of a late bleeding complication is the formation of a false aneurysm [pseudoaneurysm after partial nephrectomy].

|

Extravasation of urine:

Most urinomas after partial nephrectomy can be managed by adequate renal drainage, placement of a ureteral catheter, and bladder catheter [urinoma after partial nephrectomy].

|

Hydronephrosis:

Hydronephrosis may be caused by hematuria with clot formation.

Renal failure:

The ischemia of a solitary kidney causes transient renal failure; there is also a risk for terminal renal failure. The risk of hyperfiltration nephropathy increases if more than 50% of nephrons are resected. Early signs are proteinuria and rising creatinine concentrations. The treatment consists of reducing dietary protein and medication with ACE inhibitors.

Injury of neighboring organs:

Liver injury, spleen injury (risk of splenectomy), paralytic ileus, bowel injury, peritonitis, pancreatic tail injury with fistula, pneumothorax, and chylous fistula due to injury of intestinal lymphatic vessels.

General complications:

Wound infection, heart attack, stroke, heart failure, thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, atelectasis, pneumonia, acute renal failure.

Mortality:

Mortality due to bleeding, cardiovascular diseases, arrhythmia, acute renal failure, and pulmonary embolism is around 1–2%, with advanced tumor stage being the leading risk factor.

| Radical nephrectomy | Index | Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Blom, Jan H M; van Poppel, Hein; Maréchal, Jean M;

Jacqmin, Didier; Schröder, Fritz H; de Prijck, Linda; Sylvester, Richard &

E. O. R. T. C. Genitourinary Tract Cancer Group

Radical nephrectomy

with and without lymph-node dissection: final results of European

Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) randomized phase

3 trial 30881.

Eur Urol, 2009, 55, 28-34.

Corman u.a. 2000 CORMAN, J. M. ; PENSON,

D. F. ; HUR, K. ; KHURI, S. F. ; DALEY, J. ;

HENDERSON, W. ; KRIEGER, J. N.:

Comparison of complications after radical and partial nephrectomy:

results from the National Veterans Administration Surgical Quality

Improvement Program.

In: BJU Int

86 (2000), Nov, Nr. 7, S. 782–789

Cosentino, M.; Breda, A.; Sanguedolce, F.; Landman, J.;

Stolzenburg, J.; Verze, P.; Rassweiler, J.; Poppel, H. V.; Klingler, H.

C.; Janetschek, G.; Celia, A.; Kim, F. J.; Thalmann, G.; Nagele, U.;

Mogorovich, A.; Bolenz, C.; Knoll, T.; Porpiglia, F.; Alvarez-Maestro, M.;

Francesca, F.; Deho, F.; Eggener, S.; Abbou, C.; Meng, M. V.; Aron, M.;

Laguna, P.; Mladenov, D.; D'Addessi, A.; Bove, P.; Schiavina, R.; Cobelli,

O. D.; Merseburger, A. S.; Dalpiaz, O.; D'Ancona, F. C. H.; Polascik, T.

J.; Muschter, R.; Leppert, T. J. & Villavicencio, H.

The use of

mannitol in partial and live donor nephrectomy: an international survey.

World

J Urol, 2012.

DGU Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Nierenzellkarzinoms. https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/nierenzellkarzinom

J. Dagenais et al., “Frozen Sections for Margins During Partial Nephrectomy Do Not Influence Recurrence Rates.,” J Endourol., vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 759–764, 2018, doi: 10.1089/end.2018.0314.

Minervini, A.; Serni, S.; Tuccio, A.; Siena, G.;

Vittori, G.; Masieri, L.; Giancane, S.; Lanciotti, M.; Khorrami, S.;

Lapini, A. & Carini, M.

Simple enucleation versus radical

nephrectomy in the treatment of pT1a and pT1b renal cell carcinoma.

Ann

Surg Oncol, 2012, 19, 694-700.

Novick 2002 NOVICK, A. C.:

Nephron-sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma.

In: Annu Rev Med

53 (2002), S. 393–407

Poppel u.a. 2007 POPPEL, Hendrik V. ; POZZO,

Luigi D. ; ALBRECHT, Walter ; MATVEEV, Vsevolod ;

BONO, Aldo ; BORKOWSKI, Andrzej ; MARECHAL,

Jean-Marie ; KLOTZ, Laurence ; SKINNER, Eila ;

KEANE, Thomas ; CLAESSENS, Ilse ; SYLVESTER,

Richard ; RESEARCH for the European Organization for ;

CANCER (EORTC), Treatment of ; CANADA CLINICAL TRIALS GROUP

(NCIC CTG), National Cancer I. of ; (SWOG), Southwest Oncology G. ;

EASTERN COOPERATIVE ONCOLOGY GROUP (ECOG) the:

A prospective randomized EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the

complications of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for

low-stage renal cell carcinoma.

In: Eur Urol

51 (2007), Jun, Nr. 6, S. 1606–1615

Poppel, H. V.; Pozzo, L. D.; Albrecht, W.; Matveev, V.;

Bono, A.; Borkowski, A.; Colombel, M.; Klotz, L.; Skinner, E.; Keane, T.;

Marreaud, S.; Collette, S. & Sylvester, R.

A prospective,

randomised EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the oncologic outcome

of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage

renal cell carcinoma.

Eur Urol, 2011, 59, 543-552.

Power, N. E.; Maschino, A. C.; Savage, C.; Silberstein,

J. L.; Thorner, D.; Tarin, T.; Wong, A.; Touijer, K. A.; Russo, P. &

Coleman, J. A.

Intraoperative mannitol use does not improve long-term

renal function outcomes after minimally invasive partial nephrectomy.

Urology,

2012, 79, 821-825.

Weight, C. J.; Larson, B. T.; Fergany, A. F.; Gao, T.; Lane, B. R.; Campbell, S. C.; Kaouk, J. H.; Klein, E. A. & Novick, A. C.

Nephrectomy induced chronic renal insufficiency is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular death and death from any cause in patients with localized

cT1b renal masses.

J Urol, 2010, 183, 1317-1323

Zini, L.; Perrotte, P.; Capitanio, U.; Jeldres, C.; Shariat, S. F.; Antebi, E.; Saad, F.; Patard, J.; Montorsi, F. &

Karakiewicz, P. I.

Radical versus partial nephrectomy: effect on

overall and noncancer mortality.

Cancer, 2009, 115,

1465-1471

Deutsche Version: Offen-chirurgische Nierenteilresektion

Deutsche Version: Offen-chirurgische Nierenteilresektion

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.