You are here: Urology Textbook > Ureters > Vesicoureteral reflux

Vesicoureteral Reflux: Classification, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Definition

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a common congenital or acquired disorder of the vesicoureteral junction with reflux of urine into the upper urinary tract, which can lead to recurrent urinary tract infections, pyelonephritis with scarring, arterial hypertension, and chronic renal insufficiency. Synonyms: reflux uropathy. (Dewan et al., 1999) (Körner et al., 2010), EAU guidelines: Paediatric Urology.

Epidemiology of Vesicoureteral Reflux

The prevalence of VUR in non-symptomatic children is around 1%. In children with recurrent UTI or lower urinary tract dysfunction, the prevalence of VUR is much higher (up to 70% in children age <1, declining to 15% with age 12). Male to female ratio = 1:4. VUR can be an inherited condition: siblings and children of affected patients have an increased risk (up to 30% in twins).

Etiology of Vesicoureteral Reflux

Please see also section anatomy of the ureterovesical junction for normal anatomy.

Primary reflux:

A multifactorial congenital defect leads to premature ureter budding and fusion of the Wolffian duct with the urogenital sinus, overrotation of the ureter bud with lateralized ostia, and impaired trigonal musculature development.

Ureteral duplication:

Ureteral duplication predisposes the ureter of the lower renal pole to vesicoureteral reflux since the intravesical section is disturbed by an often-existing ureterocele of the upper pole ureter.

Secondary reflux:

Lower urinary tract dysfunction:

LUTS with high micturition pressures (dysfunctional micturition, urethral valves, neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction such as spina bifida) are a strong risk factor for high-grade vesicoureteral reflux with renal scarring.

Decompensation of the ureterovesical junction:

A borderline functioning ureterovesical junction can decompensate and cause reflux with ascending infection: e.g., UTI with bladder wall edema or during pregnancy.

Prune-Belly syndrome:

The Prune-Belly syndrome leads to disturbed development of the abdominal wall muscles and the smooth muscles of the ureters and bladder with severe vesicoureteral reflux.

Iatrogenic:

Incisions of the bladder trigonum may cause vesicoureteral reflux: prostatectomy, trigonal TURB, or resection of a ureterocele.

Classification of Vesicoureteral Reflux

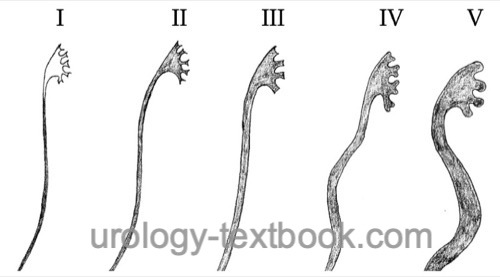

Earlier classifications differentiated between low-pressure reflux (during bladder filling) and high-pressure reflux (caused by micturition). The current classification was proposed by the Int. Reflux Study Group and depicts the possible results of the VCUG into five grades:

|

Pathophysiology

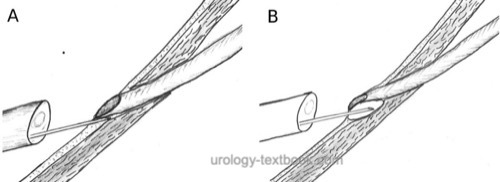

Insufficient vesicoureteral junction:

VUR is caused by the reduced length of the intramural ureter (reduced passive reflux protection, see figure below) and a weak bladder wall at the trigonum (missing active reflux protection by muscle contraction).

|

Spontaneous healing:

Due to the growth of the ureter and the increase in bladder capacity, vesicoureteral reflux improves during childhood (over the years) without therapy. Spontaneous healing is common in mild reflux and normal positioned ureteric orifices.

Recurrent urinary tract infections:

VUR leads to pendulum urine, which becomes infected. Pyelorenal reflux causes pyelonephritis. Particularly in young children (first years of life), pyelonephritis causes renal scarring.

Flat or concave papillae have an opening of the collecting tubes at a right angle, which is a risk factor for intrarenal reflux. Convex papillae have an oblique slit-like opening of the collecting tubes with less intrarenal reflux. The papillary anatomy predisposes to pyelorenal reflux at the poles.

Reflux nephropathy:

Renal scarring causes renal hypertension, proteinuria, focal segmental glomerular sclerosis, and growth delay and may lead to terminal renal insufficiency (see chronic pyelonephritis). Reflux nephropathy is responsible for 10–20% of all children with chronic renal failure.

Signs and Symptoms of Vesicoureteral Reflux

Acute pyelonephritis:

Fever, chills, flank pain, vomiting, dysuria, and pollakisuria. Sometimes without symptoms (only pyuria and bacteriuria).

Chronic pyelonephritis:

Arterial hypertension, growth delay, and symptoms of uremia.

Diagnosis of Vesicoureteral Reflux

Ultrasound imaging:

Record the width of the renal parenchyma, scars of the parenchyma (echogenic areas), the size of both kidneys, the diameter of the renal pelvis and ureter, thickness of the bladder wall, search for ureterocele or standard variants of the renal anatomy and measure postvoid residual volume. An increased resistance index in Doppler sonography indicates kidney damage with scarring (RI usually <0.7). Vesicoureteral reflux cannot be excluded based on renal ultrasound imaging.

Sonography with contrast medium:

After the instillation of air-containing contrast medium into the bladder, reflux can be visualized during or after micturition.

Voiding cystourethrography:

VCUG is the most important imaging tool for detecting vesicourethral reflux [fig. VUR in VCUG]. VCUG can be combined with urodynamics if lower urinary tract dysfunction is suspected [fig. VUR in video urodynamic study]. VCUG should only be done after sufficient treatment of urinary tract infection (at least 7–10 days after pyelonephritis); otherwise, there is a risk of false positive results. Imaging with VCUG classifies the severity of VUR; see the fig. classification of VUR. Two diagnostic problems of VCUG exist: the detection of reflux, which is insignificant for the patient, and false-negative imaging in patients with renal scarring.

|

|

Ureteral diameter ratio (UDR) in the VCUG:

The diameter of the distal ureter is divided by the distance between the cranial endplate L3 and caudal endplate L1. This ratio compensates for varying patient size and magnification factors on imaging and correlates better with prognosis (spontaneous healing, recurrent UTI, and renal scarring) than the classic classification. Low-grade reflux corresponds to a UDR less than 0.2; any increase in UDR significantly worsens prognosis, and a UDR greater than 0.35 makes spontaneous healing from reflux unlikely (Arlen et al., 2017).

Renal scintigraphy:

In addition to assessing kidney function, static kidney scintigraphy with 99mTc-DMSA can reliably diagnose renal scarring by urinary tract infections. If additional obstruction is suspected, a functional scintigraphy of the kidneys is performed with 99mTc-MAG3.

The diagnostic advantage of DMSA scintigraphy is the reliable detection of patients at risk of upper renal tract damage by vesicoureteral reflux. Some authors recommend early use of DMSA scintigraphy and do not recommend VCUG if renal scans are inconspicuous.

Diagnosis of neonatal ectasia of the renal pelvis:

Perform VCUG and/or DMSA scintigraphy if there are signs of severe VUR (renal scarring) with ultrasound imaging or after a febrile Urinary tract infections. Whether a VCUG, DMSA kidney scintigraphy, or both examinations are necessary is controversial.

Diagnostic workup after pyelonephritis:

Perform ultrasound imaging of the kidney, ureter and bladder for the first febrile Urinary tract infections. In the case of an unremarkable examination, further workup is unnecessary. Perform VCUG or DMSA scintigraphy after recurrent pyelonephritis or if sonographic abnormalities (e.g., renal scarring) are found (Roberts et al., 2011). Whether a VCUG, DMSA kidney scintigraphy, or both examinations are necessary is controversial.

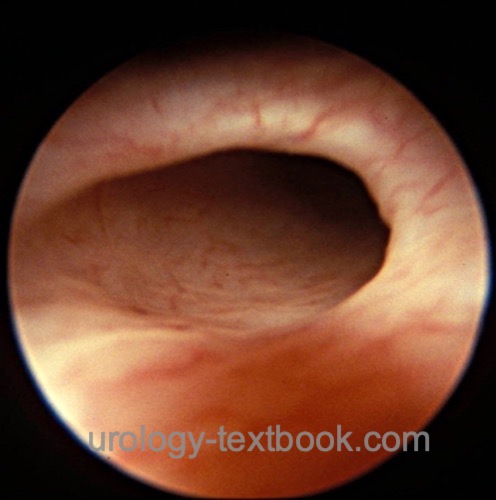

Cystoscopy:

The shape and location of the ureteric orifices can indicate vesicoureteral reflux (horseshoe or golf hole shape) and prognosis: the higher the grading, the greater the ureterotrigonal insufficiency and the worse the spontaneous healing.

- Grade 0 (Normal): like a cone or volcano with a small opening

- Grade 1 (Stadium): oval form with a circular wall

- Grade 2 (horseshoe): oval form, no medial wall

- Grade 3 (golf hole): open ostium without elevation [Abb. golf hole ureteral orifice]

|

PIC cystography:

PIC cystography uses a cystoscope to instill the contrast medium near the ostium (PIC, positioning the instillation of contrast). PIC cystography is more sensitive than conventional VCUG. The indication for PIC cystography is children with recurrent febrile urinary tract infections and no reflux in normal VCUG (Rubenstein et al., 2003). Endoscopic treatment can be done in the same session if there is evidence of reflux.

Urodynamics:

Urodynamic studies are indicated for suspected elevated detrusor pressure or lower urinary tract dysfunction [fig. VUR in video urodynamic study].

Intravenous urography:

IVU is rarely indicated. The following radiological signs are suspicious for vesicoureteral reflux: dilated ureter and pyelocalyceal system, signs of healed pyelonephritis (blunted calyces, thin cortex), ureteral duplication, and ectopic ureter. A normal IVU does not rule out reflux.

Watchful Waiting and Conservative Therapy

The therapeutic goal in treating VUR is to maintain and secure renal function by avoiding pyelonephritis. At least 50% of the children with primary reflux can be treated by watchful waiting, as trigonal insufficiency is prone to spontaneous healing, and recurrent infections are rare without risk factors. Children with recurrent urinary tract infections can remain infection-free with low-dose long-term antibiotics, reducing the risk of further renal scarring.

Indications:

Patients with vesicoureteral reflux up to grade IV, stable kidney function, and without breakthrough febrile urinary tract infections are suitable for conservative therapy.

Bacteriuria:

Bacteriuria must be treated with antibiotics, possibly with low-dose long-term antimicrobial prophylaxis with nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim, or an oral cephalosporin. The goal is to avoid febrile UTIs. Dosage: Trimethoprim 2 mg/kg bw/d, Nitrofurantoin 1–2 mg/kg bw/d, Cefaclor 10 mg/kg bw/d.

Double voiding:

Recommend regular micturition every three hours. Another voiding, after a few minutes, empties the refluxed urine.

Circumcision:

Circumcision lowers the rate of UTI in boys.

Anticholinergics:

Anticholinergic drugs increase the functional bladder capacity in patients with overactive bladder.

Close surveillance:

Urine culture is done in cases of suspected UTI and after therapy. Some centers regularly test (every three months) even symptom-free children. VCUG or renal scintigraphy are done depending on the clinical risk every 6–24 months.

Results of controlled trials:

Conservative arm of the international reflux study, randomized, n=149, follow-up 10 years of long-term antimicrobial prophylaxis in VUR III–V: 52% no longer have reflux, 25% VUR without dilatation, 23% have VUR with dilatation. Spontaneous healing of reflux is likely for VUR grade <IV, unilateral reflux, and children <5 years (Smellie et al., 2001a).Conservative arm of the Swedish reflux study, randomized, n=203 children between 1–2 years old with dilating reflux grade III–V, follow-up 2 years: 39–47% spontaneous improvement in VUR. Boys showed a good prognosis even without antibiotic prophylaxis. Girls often had recurrent UTIs, which could be avoided by antibiotic prophylaxis (Brandstroem et al., 2010).

Surgical Treatment of Vesicoureteral Reflux

Indications:

Several randomized multicenter studies have established successful conservative therapy of VUR (see above). Surgical therapy is indicated for severe reflux grade V, recurrent pyelonephritis, deterioration of kidney function, or if long-term antibiotic prophylaxis is not accepted.

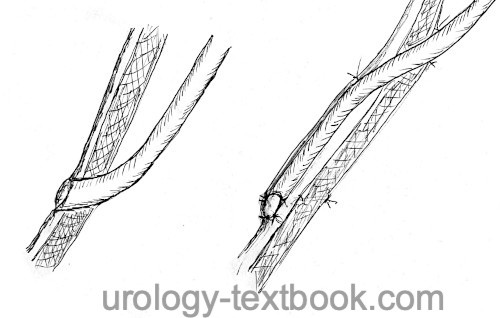

Endoscopic Treatment of Vesicoureteral Reflux:

Endoscopic injection of bulking agent to close the refluxive orifice is the least invasive surgical treatment option. The implant is injected in the submucosa layer; several injection techniques exist. The STING technique injects the bulking agent at the 6 o'clock position of the orifice until the implant closes the opening [fig. endoscopic treatment of VUR]. The HIT technique uses two injection positions 12 and 6 o'clock. After the injection, the success is checked by a cystography; further injections are possible if necessary. The HIT technique has a higher success rate controlled by cystography, but no long-term clinical data exists.

|

Compared to open surgery, retrospective trials of endoscopic treatment report almost comparable results (90% healing after two injections). However, there are no direct randomized trials. Since endoscopic treatment offers minimally invasive treatment and does not preclude open surgical treatment options in the event of failure, endoscopic therapy is a first-choice option for uncomplicated anatomy.

Ureteral reimplantation:

Ureteral reimplantation for VUR is done with either extravesical (Lich-Gregoir) or transvesical techniques (Leadbetter-Politano or Cohen). The affected kidney should have sufficient renal function (over 10% split function in renal scintigraphy). Renal function will remain stable or even improve in the long term after reimplantation. For surgical techniques and complications, see section ureteral reimplantation.

Extravesical Lich-Gregoir Ureteral Reimplantation:

Extravesical approach to the distal ureter, the incision of the bladder wall creates an extravesical tunnel without opening the mucosa; the ureter is placed in the tunnel, and the bladder wall is closed again. Possible complications are pelvic nerve injury with urinary retention after bilateral surgery.

Transvesical Leadbetter-Politano Ureteral Reimplantation:

A transvesical approach to the bladder trigone, a circumferential incision around the orifice, and mobilization of the ureter is done. A submucosal tunnel is created from the old ostium to the new hiatus 3~cm cranially. The ureter is passed through the new hiatus in the bladder and through the new tunnel to the old orifice, where the ureter is implanted with several sutures.

Transvesical Cohen Ureteral Reimplantation:

A transvesical approach to the bladder trigone, a circumferential incision around the orifice, and mobilization of the ureter is done. A submucosal tunnel is created in the contralateral direction just above the contralateral orifice. The ureter is pulled into the bladder, passed through the new tunnel, and implanted with several sutures.

Further surgical options:

The following procedures are indicated depending on the renal function and associated malformations:

Heminephroureterectomy:

Heminephroureterectomy is done for ureteral duplication with a refluxive upper pole ureter and missing renal function of the upper pole system.

Uretero-ureterostomy:

Uretero-ureterostomy is done for ureteral duplication with a refluxive upper pole ureter and significant renal function of the upper pole system: anastomosis of the caudal end of the refluxing ureter end-to-side to the competent ureter and resection of the refluxive orifice.

Nephroureterectomy:

(Laparoscopic) nephroureterectomy is an option under 10% renal split function to avoid recurrent urinary tract infections. Some authors question the need for ureter resection.

Urinary diversion:

Urinary diversion is an option for severe disorders affecting bladder capacity and endangering renal function (e.g., spina bifida).

Prognosis of Vesicoureteral Reflux

Spontaneous healing:

The following factors support spontaneous healing of vesicoureteral reflux or a benign course: low-grade reflux, missing dilatation of the distal ureter, male sex, unilateral reflux, no disorders of urinary bladder or bowel function, no renal scarring, and high urinary bladder volume at the onset of reflux.

| Ureterocele | Index | Megaureter |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

A. M. Arlen, A. J. Kirsch, T. Leong, and C. S. Cooper, “Validation of the ureteral diameter ratio for predicting early spontaneous resolution of primary vesicoureteral reflux.,” J. Pediatr. Urol., vol. 13, no. 4, p. 383, 2017.

Per Brandströmm and Tryggve Neveus and Rune Sixt and Eira Stokland and Ulf Jodal and Sverker Hansson, “The Swedish reflux trial in children: IV. Renal damage.,” vol. 184, no. 1, pp. 292–297, 2010.

Dewan 1999 DEWAN, P. A.:

Vesicoureteric reflux: the evolution of the understanding of the

anatomy and the development of radiology.

In: Eur Urol

36 (1999), Nr. 6, S. 559–64

EAU guidelines: Paediatric Urology

Körner, I. & Steffens, J.

[Treatment of

vesicoureteral reflux in childhood].

Urologe A, 2010,

49, 1248-1253

Olbing u.a. 2003 OLBING, H. ; SMELLIE, J. M. ;

JODAL, U. ; LAX, H.:

New renal scars in children with severe VUR: a 10–year study of

randomized treatment.

In: Pediatr Nephrol

18 (2003), Nr. 11, S. 1128–31

Rubenstein, J. N.; Maizels, M.; Kim, S. C. & Houston,

J. T.

The PIC cystogram: a novel approach to identify "occult"

vesicoureteral reflux in children with febrile urinary tract infections.

J

Urol, 2003, 169, 2339-2343.

Smellie u.a. 2001 SMELLIE, J. M. ; JODAL, U. ;

LAX, H. ; MOBIUS, T. T. ; HIRCHE, H. ;

OLBING, H.:

Outcome at 10 years of severe vesicoureteric reflux managed

medically: Report of the International Reflux Study in Children.

In: J Pediatr

139 (2001), Nr. 5, S. 656–63

Wingen u.a. 1999 WINGEN, A. M. ; KOSKIMIES,

O. ; OLBING, H. ; SEPPANEN, J. ; TAMMINEN-MOBIUS,

T.:

Growth and weight gain in children with vesicoureteral reflux

receiving medical versus surgical treatment: 10–year results of a

prospective, randomized study. International Reflux Study in Children

(European Branch).

In: Acta Paediatr

88 (1999), Nr. 1, S. 56–61

Deutsche Version: Vesikoureteraler Reflux

Deutsche Version: Vesikoureteraler Reflux

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.