You are here: Urology Textbook > Bladder > Bladder cancer Symptoms and diagnosis

Bladder cancer: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Imaging

Review Literature: EAU guidelines superficial bladder cancer. EAU guidelines of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. German S3 guidelines bladder carcinoma Harnblasenkarzinom.

- Bladder carcinoma: Definition, Epidemiology and Etiology

- Bladder carcinoma: Pathology and TNM tumor stages

- Bladder carcinoma: Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Bladder carcinoma: Surgical Treatment

- Bladder carcinoma: Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy of Metastases

Signs and Symptoms of Bladder Cancer

Symptoms of Superficial Bladder Carcinoma:

Painless hematuria, rather intermittently, is the leading symptom (85–90%). Irritative symptoms like dysuria, frequency and urgency are not as common (30%). Most of the superficial bladder cancers are symptomatic.

Signs and Symptoms of Advanced Bladder Cancer:

Abdominal mass, bone pain, flank pain, hydronephrosis, weight loss, and night sweats.

Diagnostic Workup of Bladder Cancer

Laboratory tests

Urinary sediment:

Unspecific sign in urine analysis: Microhematuria or macrohematuria.

Urine cytology:

Microscopic examination of exfoliated urothelial cells of the urine can reliably identify G2 and G3 cells of bladder carcinoma. Cells of well-differentiated tumors are less often exfoliated and are harder to distinguish from cells of inflammatory lesions.

Urine markers:

Urine markers improve the detection of bladder cancer and may reduce the frequency of cystoscopy in the follow-up of superficial tumors. The exact role of urine markers in the diagnostic workup is unclear; see Tab. sensitivity and specificity of urine markers and section experimental diagnostics below.

| Urine marker | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| NMP 22 | 47–100% | 55–98% |

| BTA stat | 29–83% | 56–86% |

| ImmunoCyt | 52–100% | 63–75% |

Laboratory tests:

Blood count may reveal hypochromic anemia and iron deficiency due to chronic bleeding. Tumor anemia is possible in advanced disease. Elevated liver enzymes are a symptom of liver metastasis. Hydronephrosis may cause high creatinine and urea serum concentrations. Bone metastases cause elevated AP.

Imaging of Bladder Cancer

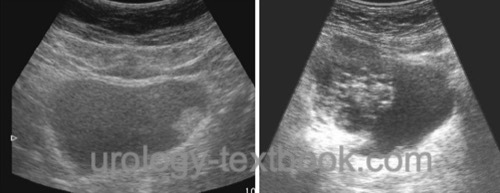

Ultrasound imaging:

Ultrasound imaging is best done with a full bladder. Bladder cancer appears as an echogenic mass that protrudes into the lumen [fig. ultrasound imaging of bladder cancer]. Invasive bladder cancer may be suspected if the normally highly echogenic bladder wall is interrupted by less echogenic tissue from the bladder tumor (false-negative in 40%, false-positive in 10%). Ultrasonography of the kidneys is done to detect hydronephrosis or a mass in the renal sinus as signs of upper tract urothelial cancer.

|

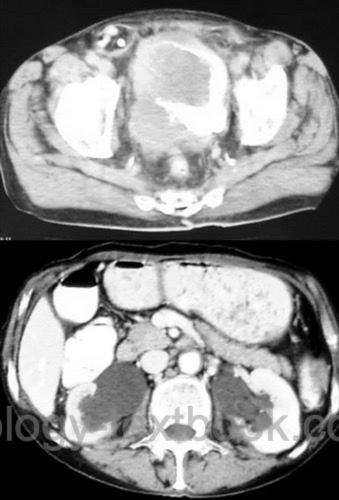

Imaging of the upper urinary tract:

Imaging of the upper urinary tract is necessary after initial diagnosis of bladder carcinoma. The most suitable method is a contrast-enhancing CT (excretion phase). Alternative imaging option are an MRI abdomen with excretion phase or an intravenous urography [fig. IVP of an advanced bladder cancer].

|

Staging of invasive bladder cancer:

CT scan of the pelvis, abdomen and chest is standard to stage invasive bladder cancer [fig. CT scan of advanced bladder carcinoma]. Alternative option for staging are an abdominal MRI and chest X-ray.

|

Further facultative imaging: bone scintigraphy (for patients with bone pain or elevated AP), ultrasound of the liver (if CT or MRI is not available). PET has no additional value in staging of bladder carcinoma.

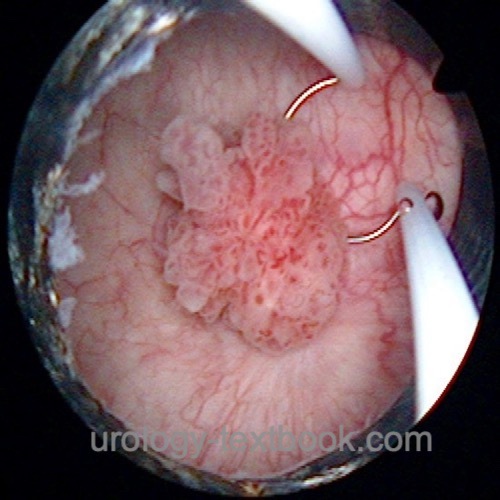

Cystoscopy and transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB)

Cystoscopy is the single most important procedure to diagnose bladder cancer. The location, size, and appearance of the tumor are documented. Bladder tumors or suspicious tissue are treated by transurethral resection of the bladder (see section TURB) with deep resection into the tunica muscularis [fig. cystoscopy of bladder carcinoma]. Quadrant biopsy of the urinary bladder is a diagnostic procedure for patients with suspected high-grade bladder carcinoma (e.g., history of high-grade tumor or urine cytology with high-grade cells): small samples are taken from the anterior wall, the two side walls, the posterior bladder wall, and prostatic urethra.

|

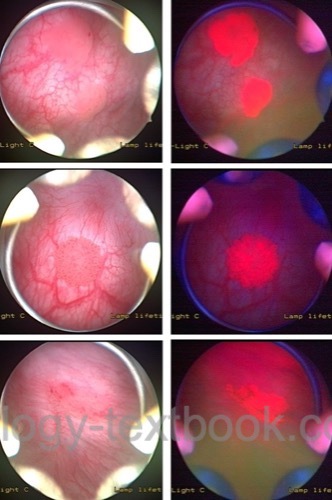

Fluorescence cystoscopy:

Standard cystoscopy is not able to visualize all forms of bladder carcinoma. Especially flat high-grade lesions may be overseen or may look like normal urothelium. The fluorescence cystoscopy improves the detection of CIS by 25–30%. The bladder is incubated for one hour with hexaminolevulinate (HAL) and the cystoscopy is done with blue light (375–440 nm wavelength). Hexaminolevulinate is a photosensitive porphyrin that accumulates preferentially in tissue with a high turnover of cells, like neoplastic tissues, but also in inflammatory lesions. Tissues with a high concentration of HAL glow red under blue light. Clinically relevant improvement in sensitivity and specificity has been proved in several randomized trials (Jocham et al., 2005). However, in recent randomized controlled studies, this does not reduce the long-term recurrence rate (Heer et al., 2022).

|

Experimental Diagnostic Techniques

Urine markers

Urine markers for the diagnosis of bladder cancer: urinary bladder cancer antigen (UBC), BTA stat, nuclear matrix protein (NMP22), telomerase, survivin, multi-target FISH (UroVysion), loss of chromosomes. No marker has sufficient sensitivity and specificity to replace cystoscopy or urine cytology.

Cystoscopy with narrow-band imaging:

Cystoscopy with narrow-band imaging improved tumor detection rates compared to standard cystoscopy. Prospective trials comparing recurrence and progression are not available.

Other diagnostic techniques:

Urine immunocytology improves the results of standard urine cytology. Detection of cytokeratin in serum or bone marrow with the help of PCR correlates with an advanced tumor stage.

Differential Diagnosis of Bladder Tumors

- Benign and malignant bladder tumors: see section pathology

- Inflammation or infection

- Tissue reaction due to foreign bodies, catheter, or bladder stones.

- Schistosomiasis

- Bladder fistula (birth trauma, diverticulitis, Crohn disease, rectal cancer)

- Endometriosis

| Bladder cancer: pathology | Index | Bladder cancer treatment |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Abol-Enein, H.

Infection: is it a cause of bladder

cancer?

Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl, 2008, 79-84.

Amin und Young 1997 AMIN, M. B. ; YOUNG, R. H.:

Primary carcinomas of the urethra.

In: Semin Diagn Pathol

14 (1997), Nr. 2, S. 147–60

Babjuk, M.; Burger, M.; Compérat, E.; Gonter, P.;

Mostafid, A.; Palou, J.; van Rhijn, B.; Rouprêt, M.; Shariata, S.;

Sylvester, R. & Zigeuner, R.

Non-muscle-invasive Bladder CancerEAU

Guidelines, 2020 https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer/

Brinkman, M. & Zeegers, M. P.

Nutrition, total

fluid and bladder cancer.

Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl, 2008,

25-36.

Cohn, J. A.; Vekhter, B.; Lyttle, C.; Steinberg,

G. D. & Large, M. C.

Sex disparities in diagnosis of bladder cancer

after initial presentation with hematuria: a nationwide claims-based

investigation.

Cancer, 2014, 120, 555-561

DGU; DKG; DKG & Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie S3-Leitlinie (Langfassung): Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge des Harnblasenkarzinoms. https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/harnblasenkarzinom/

Helpap und Kollermann 2000 HELPAP, B. ;

KOLLERMANN, J.:

[Revisions in the WHO histological classification of urothelial

bladder tumors and flat urothelial lesions].

In: Pathologe

21 (2000), Nr. 3, S. 211–7

IARC (2004) Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Volume 83. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. World Health Organization.

Kalble 2001 KALBLE, T.:

[Etiopathology, risk factors, environmental influences and

epidemiology of bladder cancer].

In: Urologe A

40 (2001), Nr. 6, S. 447–50

Kataja und Pavlidis 2005 KATAJA, V. V. ;

PAVLIDIS, N.:

ESMO Minimum Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and

follow-up of invasive bladder cancer.

In: Ann Oncol

16 Suppl 1 (2005), S. i43–4

Krieg und Hoffman 1999 KRIEG, R. ; HOFFMAN, R.:

Current management of unusual genitourinary cancers. Part 2: Urethral

cancer.

In: Oncology (Williston Park)

13 (1999), Nr. 11, S. 1511–7, 1520; discussion 1523–4

Lammers, R. J. M.; Witjes, W. P. J.; Hendricksen, K.;

Caris, C. T. M.; Janzing-Pastors, M. H. C. & Witjes, J. A.

Smoking

status is a risk factor for recurrence after transurethral resection of

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Eur Urol, 2011,

60, 713-720

Lampel und Thuroff 1998a LAMPEL, A. ;

THUROFF, J. W.:

[Bladder carcinoma 1: Radical cystectomy, neoadjuvant and adjuvant

therapy modalities].

In: Urologe A

37 (1998), Nr. 1, S. 93–101

Lampel und Thuroff 1998b LAMPEL, A. ;

THUROFF, J. W.:

[Bladder carcinoma. 2: Urinary diversion].

In: Urologe A

37 (1998), Nr. 2, S. W207–20

Leppert u.a. 2006 LEPPERT, J. T. ; SHVARTS,

O. ; KAWAOKA, K. ; LIEBERMAN, R. ; BELLDEGRUN,

A. S. ; PANTUCK, A. J.:

Prevention of bladder cancer: a review.

In: Eur Urol

49 (2006), Nr. 2, S. 226–34

Liu, S.; Yang, T.; Na, R.; Hu, M.; Zhang, L.; Fu,

Y.; Jiang, H. & Ding, Q.

The impact of female gender on bladder

cancer-specific death risk after radical cystectomy: a meta-analysis of

27,912 patients.

International urology and nephrology, 2015,

47, 951-958

Michaud u.a. 1999 MICHAUD, D. S. ; SPIEGELMAN,

D. ; CLINTON, S. K. ; RIMM, E. B. ; CURHAN,

G. C. ; WILLETT, W. C. ; GIOVANNUCCI, E. L.:

Fluid intake and the risk of bladder cancer in men.

In: N Engl J Med

340 (1999), Nr. 18, S. 1390–7

Plna und Hemminki 2001 PLNA, K. ; HEMMINKI, K.:

Familial bladder cancer in the National Swedish Family Cancer

Database.

In: J Urol

166 (2001), Nr. 6, S. 2129–33

Rajan u.a. 1993 RAJAN, N. ; TUCCI, P. ;

MALLOUH, C. ; CHOUDHURY, M.:

Carcinoma in female urethral diverticulum: case reports and review of

management.

In: J Urol

150 (1993), Nr. 6, S. 1911–4

Robert-Koch-Institut (2015) Krebs in Deutschland 2011/2012. www.krebsdaten.de

Stein u.a. 2001 STEIN, J. P. ; LIESKOVSKY,

G. ; COTE, R. ; GROSHEN, S. ; FENG, A. C. ;

BOYD, S. ; SKINNER, E. ; BOCHNER, B. ;

THANGATHURAI, D. ; MIKHAIL, M. ; RAGHAVAN, D. ;

SKINNER, D. G.:

Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer:

long-term results in 1054 patients.

In: J Clin Oncol

19 (2001), Nr. 3, S. 666–75

Weissbach 2001 WEISSBACH, L.:

[Palliation of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder].

In: Urologe A

40 (2001), Nr. 6, S. 475–9

Witjes, J.; Compérat, E.; Cowan, N.; Gakis, G.;

Hernánde, V.; Lebret, T.; Lorch, A.; van der Heijden, A. & Ribal, M.

Muscle-invasive

and Metastatic Bladder Cancer

EAU Guidelines, 2020 https://uroweb.org/guidelines/bladder-cancer-muscle-invasive-and-metastatic/

Deutsche Version: Symptome und Diagnose des Harnblasenkarzinoms

Deutsche Version: Symptome und Diagnose des Harnblasenkarzinoms

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.