You are here: Urology Textbook > Testes > Testicular torsion

Testicular Torsion: Diagnosis and Treatment

Definition of Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a mostly spontaneous torsion of the testicle around the spermatic cord with consecutive ischemia.

Epidemiology of Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is possible at any time of life. Testicular torsion is most frequent in children (before the second year of life) and adolescents (between 15–20 years of age). The incidence of testicular torsion in boys under the age of 18 is 4–7/100.000. In 30–40% of patients, testicular torsion leads to an orchiectomy (Pogorelic et al., 2022).

Etiology and Pathophysiology of Testicular Torsion

Causes of Testicular Torsion

Abnormal mobility of the testicle causes testicular torsion. Cremasteric contraction causes a rotational force to the testes and can induce testicular torsion, as also manipulation or testicular trauma may trigger a torsion.

Ipsilateral Testicular Damage after Torsion

The torsion of the testis leads to impaired venous drainage and hemorrhagic necrosis of the testicular tissue. The testicular tissue is irreversibly damaged after eight hours of complete torsion. The ischemic damage may be significantly lower after incomplete torsion, and testis preservation may be feasible after longer intervals. Detorsion leads to an additional reperfusion injury of the tissue through the induction of oxidative stress.

Contralateral Testicular Damage after Torsion

Subfertility may develop after testicular torsion; the prevalence and mechanisms are unclear and controversial. Possible mechanisms are reflectory sympathetic vasocontriction with subsequent ischemia and damage to the blood-testis barrier with formation of anti-sperm antibodies. In addition, testicular torsion may be a form of congenital testicular dysgenesis, explaining the bilateral risk of torsion and reduced testicular function found in patients after torsion (Jacobsen et al., 2020).

Pathology of Testicular torsion

Testicular torsion can be separated into intravaginal torsion (torsion of the spermatic cord within the tunica vaginalis) and extravaginal torsion (torsion of the spermatic cord outside the tunica vaginalis). Untreated testicular torsion leads to hemorrhagic necrosis of the testis since the torsion of the spermatic cord first compresses the venous supply.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Signs and Symptoms of Testicular Torsion

- Sudden testicular pain.

- Abnormal high position of the testes in the scrotum, with abnormal transverse direction.

- Radiation of testicular pain to the ipsilateral lower abdomen.

- Nausea and vomiting are possible.

- Missing cremasteric reflex.

- The Prehn sign is negative: same or more significant pain with elevation of the testis. The Prehn sign is unreliable.

- Precursors of testicular torsion are similar, less painful events.

- Scrotal swelling and infection are possible in delayed presentation.

Diagnosis of Testicular Torsion

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory Tests

Urine analysis, complete blood count, and CRP to rule out infection as a differential diagnosis.

Testicular Ultrasound Imaging

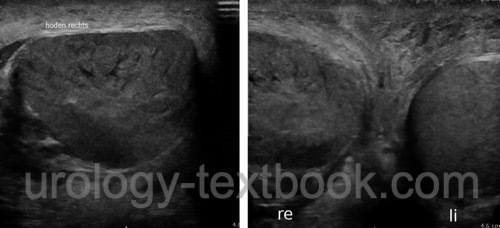

In untreated testicular torsion with delayed presentation, conventional ultrasound imaging shows inhomogeneities of the testicular tissue. Differentiation from a testicular tumor might become difficult. Imaging of the spermatic cord can visualize the cord twist as a snail-shaped mass.

|

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Testicular Doppler-Sonography

Doppler ultrasound of the testis can detect a lack of blood flow in the testis with 90% sensitivity and 99% specificity, 1% false positive results. Some studies found worse results. If the patient presents with typical signs and symptoms of testicular torsion, the detection of a testicular blood flow should be questioned.

Crucial for the proper assessment is the Doppler study of intratesticular vessels, the study of capsule or scrotum vessels is irrelevant. If an arterial Doppler signal in the testis disappears by compressing the spermatic cord at the external inguinal ring, testicular blood flow is proved. If the signal is not influenced by spermatic cord compression, an irrelevant scrotal vessel is detected. Testicular vessels have a high end-diastolic blood flow; normally, the resistive index (RI) is below 0.7. Higher RI values (decreasing diastolic blood flow) are signs of a partial testicular torsion.

Scintigraphy of the Testis

Comparative studies found similar results between scintigraphy of the testis and Doppler ultrasound imaging. The disadvantages of testicular scintigraphy are the limited availability, long examination times, and difficult interpretation in young children with small scrotums.

Differential Diagnosis of Testicular Torsion

- Torsion of testicular appendage

- Epididymitis

- Orchitis

- Testicular trauma

- Inguinal hernia

- Germ cell tumor

- Hydroceles

- Spermatocele

- Varicocele

- Hematocele

Treatment of Testicular Torsion

Surgical Detorsion and Orchidopexy

Immediate surgical exploration, detorsion, and orchidopexy should be offered in suspected testicular torsion, even if the diagnosis is only possible. Scrotal exploration is done with bilateral transverse incisions or a median raphe incision [fig. surgical exploration in suspected testicular torsion]. With a transverse incision, a dartos pouch can be done before opening the tunica vaginalis of the testis. After the detorsion of the testis, the organ is examined for viability. Proceed with orchidopexy when the testis shows recovery and is viable. Orchidopexy is done with a dartos pouch as in cryptorchism treatment, or fine nonabsorbable sutures are used for sutures of the tunica vaginalis to the tunica dartos. Orchiectomy is necessary for necrotic testis without bleeding after several minutes of warming.

Immediate prophylactic fixation of the opposite testis is recommended after a confirmed testicular torsion. In cases with severe necrosis and infection, the contralateral fixation should be postponed until ipsilateral wound healing is complete.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Manual Detorsion of a Testicular Torsion

Manual Detorsion can be attempted as a provisional emergency aid when scrotal swelling is moderate and the patient tolerates the manipulation (after local anesthesia of the spermatic cord). The left testis is often rotated counterclockwise, and the right testis is rotated clockwise (viewed from the patient's feet). Manual detorsion is achieved with rotation of the ventral circumference laterally (to the thigh) to compensate for the most frequent rotation direction (like opening a book). Manual detorsion is unsafe since testicular torsion is also possible in the opposite direction. The success of the manual detorsion should lead to clinical improvement and visible testicular perfusion in Doppler ultrasound imaging. After successful manual detorsion, scrotal orchidopexy of both sides should be done within the next few days.

| Testicular diseases | Index | Hydatide torsion |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Cuckow und Frank 2000 CUCKOW, P. M. ; FRANK,

J. D.:

Torsion of the testis.

In: BJU Int

86 (2000), Nr. 3, S. 349–53

Frank und O’Brien 2002 FRANK, J. D. ; O’BRIEN,

M.:

Fixation of the testis.

In: BJU Int

89 (2002), Nr. 4, S. 331–3

Z. Pogorelić, S. Anand, L. Artuković, and N. Krishnan, “Comparison of the outcomes of testicular torsion among children presenting during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic versus the pre-pandemic period: A systematic review and meta-analysis.,” J Pediatr Urol., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 202–209, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.01.005.

C. Radmayr, G. Bogaert, H. S. Dogan, and S. Tekgül, “EAU Guidelines: Paediatric Urology.” [Online]. Available: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/

Visser und Heyns 2003 VISSER, A. J. ; HEYNS,

C. F.:

Testicular function after torsion of the spermatic cord.

In: BJU Int

92 (2003), Nr. 3, S. 200–3

Deutsche Version: Hodentorsion

Deutsche Version: Hodentorsion

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.