You are here: Urology Textbook > Urologic examinations > Blood tests > Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA)

Prostate-Specific Antigen: PSA Screening Test

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a tissue kallikrein (formal name: human kallikrein 3 = hK3): glycoprotein with 237 amino acids, molecular mass 33000 dalton. PSA is produced in an inactive preform in the gland cell (PreProPSA), splitting creates ProPSA (still inactive), which is then secreted into the seminal fluid. Further cleavage (by kallikrein 2, hK2) activates PSA. PSA is a serine protease and liquifies the seminal coagulum.

Biochemistry of PSA

The main amount of PSA is secreted into the seminal fluid, the concentration in the blood is smaller by a factor of 1000000, normally below 4 ng/ml. PSA is also detectable in low levels in breast, breast milk, endometrium and kidney and adrenal tumors without clinical significance. 1 g of prostate tissue increases PSA by up to 0.15 ng/ml, while prostate cancer tissue releases about 10–30fold amount of PSA. There is a significant overlap in PSA concentrations in patients with BPH or prostate cancer.

Active PSA is inactivated in the seminal fluid by proteolysis to inactive PSA. Inactive PSA that enters the bloodstream circulates as free PSA (fPSA, 10–30%). Active PSA that enters the bloodstream is inactivated by a complex binding with protease inhibitors such as α1-antichymotrypsin (ACT) or α2-macroglobulin (AMG, A2M) (cPSA, 70–90%). Total PSA (tPSA) is thus present in the blood as free PSA (fPSA) and as complexed PSA (cPSA).

Bound PSA is degraded in the liver, glomerular filtration does not take place due to size. The half-life is 2–3 days. The half-life of free PSA is significantly shorter, as a glomerular filtration is possible (Stephan et al., 2000).

Indication:

PSA is used as a tumor marker or disease marker (Polascik et al., 1999).

Tumor marker:

Screening, prognosis and follow-up of prostate cancer (see section prostate cancer).

Disease marker:

Diagnosis and follow-up of bacterial prostatitis. Marker of progression in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Laboratory Test Method:

The PSA molecule has 5 epitopes which are partially occluded by protein binding or become accessible only after inactivation. This allows the measurement of tPSA, fPSA and cPSA by using appropriate antibodies (Sandwich ELISA). Semi-quantitative test strips are not suitable for the early detection of prostate cancer, but are commercially available.

Standard Value in Screening:

Previously, a rigid PSA standard value of 4 ng/ml was used to initiate prostate biopsy. A rigid standard value, however, led to a poor predictive accuracy of the PSA resulting in prostate biopsies revealing BPH or overlooking prostate cancer.

The predictive value of PSA can be improved by combining age-specific reference ranges, PSA velocity and free PSA (see below). An increased PSA concentration should be controlled taking into account confounding factors.

False-Negative PSA Test:

PSA test result below the cut-off value, but prostate cancer is present. Causes are prostate cancer with low PSA expression, anti-androgen therapy, finasteride and other 5α-reductase inhibitors. Therapy with finasteride over 12 months halves the PSA concentration (Guess et al., 1993). Other causes include previous prostate surgery like such as TURP or simple prostatectomy.

False-Positive PSA Test:

PSA test result above the cut-off value, but prostate cancer is not present. The most important causes are benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, urinary retention, trauma, sexual activity and excessive cycling (Tchetgen et al., 1996). After iatrogenic manipulation, such as cystoscopy or catheterization, a PSA increase is possible (Oesterling et al., 1993b). A digital-rectal examination leads to a small increase in PSA (average by 0.4 ng/ml) (Chybowski et al., 1992) (Crawford et al., 1992). After a prostate biopsy, the normalization of the PSA level lasts up to 4 weeks (Oesterling et al., 1993b).

Improvement of Sensitivity and Specificity of PSA Screening:

The above mentioned facts explain the low sensitivity and specificity of PSA screening. An improvement can be achieved by using age-specific reference ranges, free PSA concentration (fPSA), PSA-density, PSA-velocity and observing a longer time intervall of PSA results.

Age-specific Reference Ranges:

Age-specific reference ranges help to avoid unnecessary prostate biopsies in elderly patients and may identify potentiell aggressive tumors in young patients (Oesterling et al., 1993), this is however controversial (Littrup et al., 1994):

- <50 years: <2,5 ng/ml

- 50–59 years: < 3,5 ng/ml

- 60–69 years: < 4,5 ng/ml

- 70–79 years: < 6,5 ng/ml

Free PSA (fPSA):

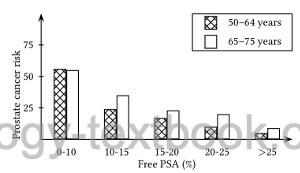

As the proportion of fPSA decreases, the probability of prostate cancer increases (Polascik et al., 1999). The fPSA is used to increase the sensitivity of the PSA screening in the range of 2–4 ng/ml. Furthermore, fPSA improves the specificity of PSA screening in the range of 4–10 ng/ml. An fPSA fraction of more than 20–25% is considered unsuspicious for a prostate carcinoma [see fig. fPSA_diagram]. Numerous studies have shown a correlation between low fPSA levels and aggressive prostate cancer before curative therapy (Masieri u.a., 2012).

|

Risk of prostate cancer depending on age and fPSA concentration in the PSA range 4–10 ng/ml |

Free PSA consists of different isoforms, the incorrectly cleaved and therefore inactive proPSA (more precisely: isoform [-2] proPSA) achieved better predictive values than tPSA or fPSA in some studies (Lazzeri u.a., 2013) (Furuya u.a., 2017). The test is not yet established.

Complexed PSA (cPSA):

Above mentioned test assays can detect bound PSA to macromolecules (complexed PSA). In contrast to free PSA (fPSA), cPSA is increased in prostate cancer. The determination of cPSA has not yet become established in everyday clinical practice, a clear advantage over fPSA is still pending.

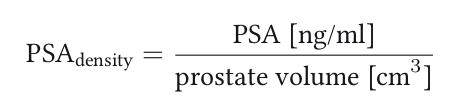

PSA-Density (PSAD):

In patients with a large prostate (BPH) and PSA levels of 4–10 ng/ml, attention to PSA density may avoid unnecessary prostate biopsy. The PSA density is calculated according to the following formula:

|

Prostate cancer risk is increased above a PSA density of 0.1–0.15. But even with unsuspicious PSA density, significant prostate carcinomas are found (Catalona et al., 1994) (Catalona et al., 1997a).

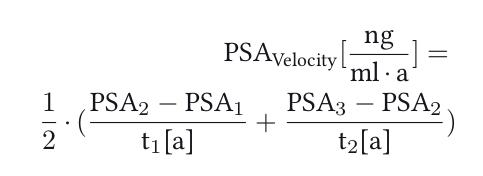

PSA-Velocity (PSAV):

PSA-velocity can be calculated with three PSA concentrations (PSA1–3) within two time intervals (t1–2, unit in years) with the following formula. A PSA-velocity of more than 0,75 ng/ml/year is suspicious for prostate cancer:

|

PSA-Velocity increases sensitivity and specificity of PSA screening (Carter et al., 1992) (Polascik et al., 1999). Other authors recommend a cut-off value of 0,5 ng/ml/year for using the PSA-velocity (Berger u.a., 2007). In contrast, PSA-velocity was not found helpful in the european screening study (Roobol u.a., 2004b).

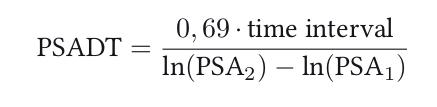

PSA-Doubling Time (PSADT):

PSA-doubling time is a good parameter to assess the prognosis of a PSA increase after curative therapy: a doubling time under 6 to 12 months indicates a poor prognosis (metastasis, death). Calculating the PSA doubling time is complex, and accurate calculations can only be achieved with multiple PSA values over a maximum of 12 months. Several formulas exist in the literature (Arlen u.a., 2008).

As an approximation, the following formula can be used, requiring two PSA concentrations (PSA1 and PSA2) at least 3 months apart. The formula uses the natural logarithm ln to the base of the mathematical constant e. The time interval should be given in months, as a result the formula calculates the PSA-doubling time (PSADT) in months:

|

| GnRH test | Index | AFP |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Guder, W. G. & Nolte, J. Das Laborbuch für Klinik und PraxisUrban + Fischer, 2009

Köhn, F.-M. (2004). [diagnosis and therapy of hypogonadism in adult males].

Urologe A, 43(12):1563-81; quiz 1582–3.

Trottmann, M., Dickmann, M., Stief, C. G., and Becker, A. J. (2010).

[laboratory workup of testosterone].

Urologe A, 49(1):11–15.

Siegenthaler 1988 SIEGENTHALER, W. ;

SIEGENTHALER, W. (Hrsg.):

Differentialdiagnose innerer Krankheiten.

Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, New York., 1988

Deutsche Version: Prostataspezifisches Antigen (PSA)

Deutsche Version: Prostataspezifisches Antigen (PSA)

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.