You are here: Urology Textbook > Kidneys > Urogenital tuberculosis

Urogenital Tuberculosis: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment

Definition of Urogenital Tuberculosis

Urogenital tuberculosis is mostly a chronic infection of the urogenital organs with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Review literature: (Bergstermann and Häußlinger, 2002) (Lenk and Schroeder, 2001) (Petersen et al., 1993) (Wise and Marella, 2003).

Consumption:

Due to weight loss, the historical term for advanced tuberculosis is consumption.

Epidemiology of Tuberculosis

The WHO estimates that one-quarter of humanity is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In 2018, there were 10 million new clinically significant infections and 1.5 million deaths caused by TB.

Tuberculosis epidemiology in Germany:

The incidence and mortality of tuberculosis in Germany is declining. Figures from 2010: 4330 new cases (1999: 9800 new cases). Incidence 5/100000. Mortality is 0.2 /100000, of which 2/3 are older than 65. Male to female ratio is 2:1. The proportion of urogenital tuberculosis among new cases is 4%. The European prevalence of renal tuberculosis in autopsy statistics is 0.6 to 0.9%. Tuberculosis is a notifiable disease in Germany.

Etiology of Urogenital Tuberculosis

Bacteria of tuberculosis:

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a 1–2 microns long immobile bacillus: acid-resistant, intracellular persistence in phagocytes, and a doubling time of 1--2 days.

Transmission of tuberculosis:

Tuberculosis is usually a droplet infection of the lungs. Of the infected patients, 5–10% develop clinically significant active tuberculosis, with relevant risk factors (see below) even more. 50% of active tuberculosis occur within the first two years after infection.

In developing countries, primary intestinal tract infection via the milk of infected cows still plays a significant role. Tuberculosis can rarely be transmitted through the skin (e.g., during autopsy or sexual intercourse).

Risk factors for active tuberculosis:

- Immigrants

- Alcoholism

- Old age

- AIDS

- Diabetes mellitus

- Steroid therapy

- Intravenous drug abuse

- Smoking

- Lung diseases: silicosis, COPD

- Malnutrition

- Malignant diseases

- Gastric resection

- Crowding, e.g., prisons

Pathophysiology of Tuberculosis

Intracellular persistence of tuberculosis bacteria:

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a typical example of a successful intracellular bacterium. The persistence of the pathogen occurs in macrophages. Several mechanisms protect mycobacteria from enzymatic digestion in macrophages: suppression of oxygen free radicals, suppression of phagosome acidification, and waxy cell wall.

Primary complex of tuberculosis:

After the initial infection of the lung tissue and lymph nodes, the immune system gains control of the pathogen, and the disease is isolated within granulomas. Depending on the immune status, a latent or clinically significant infection follows the primary manifestation.

Progressive disease of tuberculosis:

Recurrent bacteremia from the primary complex leads to additional foci (minimal lesions) of the lungs and other organs; they are the starting points for future recurrences. Clinical significant infection or recurrence occurs with poor immune status; see risk factors mentioned above.

Pathology of Urogenital Tuberculosis

Macroscopic pathology of urogenital tuberculosis:

Minimal lesions of tuberculosis:

Minimal lesions are initially caseating tuberculomas; with sufficient control of the immune system, they lead to calcified lesions. The immune status determines the further course.

Renal manifestation of tuberculosis:

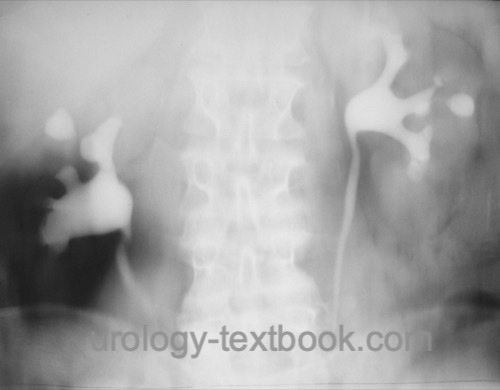

A chronic inflammatory process with granulomas, scarring, calcification, and caseating necrosis begins upon activation of tuberculosis due to a poor immune status. The sloughing of caseous material via the collecting systems leads to the deformation of the pyelocalyceal system, calyx cavities [fig. renal tuberculosis in IVU] and papillary necrosis. Scarring leads to calyceal infundibular narrowing and strictures of the ureteropelvic junction with hydronephrosis.

The final stage of renal manifestation (and destruction) is the "cement" kidney: complete caseating necrosis without any renal function.

Ureteral manifestation of tuberculosis:

Ureteral strictures lead to hydronephrosis and loss of renal function.

Tuberculosis of the urinary bladder:

Tuberculosis of the urinary bladder almost always arises secondarily from renal lesions. The initial lesions are edema and swelling of the ostium; scarring of the ostium leads to hydronephrosis. Later, bullous-ulcerative tuberculosis lesions develop in the bladder mucosa, which heal with scarring. The scarred contracted bladder is the final manifestation of tuberculosis of the urinary bladder.

Tuberculosis of the epididymis and testis:

Initial tuberculomas occur in the epididymis via the bloodstream; a renal manifestation is not mandatory. The disease progresses via the vas deferens (beaded vas), the testis, and the prostate. The lesions of the epididymis may ulcerate through the scrotal skin.

Tuberculosis of the penis:

The penile skin is rarely the primary site of infection after sex with an infected partner with genital or oral manifestations of tuberculosis. The initial lesion is a penile tumor or ulcer resembling penile cancer.

The secondary manifestation of tuberculosis into the skin of the penis is rare and corresponds to lupus vulgaris (tuberculosis) of the skin. Untreated lupus vulgaris results in a destructive infection of the penis.

Histology of tuberculosis:

Depending on the immune status, different forms of granulomas (tuberculomas) develop:

- Poor immune status (anergic): caseous necrosis without response of the immune system.

- Normal immune status: caseous necrosis surrounded by macrophages (epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells)

- Good immune status (hypererg): epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells without central necrosis.

Signs and Symptoms of Urogenital Tuberculosis

Symptoms from the urogenital tract:

Signs and symptoms are lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), flank pain, (micro) hematuria, and arterial hypertension. 20% of patients with urogenital tuberculosis do not report any bother.

Epididymitis presents with swelling, pain, and redness of the scrotum. Infertility is a common sequela. The manifestation of tuberculosis of the penis is rare and presents with an ulcer (primary infection) or destructive infection (lupus vulgaris).

Symptoms from the respiratory tract:

Fever, cough, night sweats, erythema nodosum, pleurodynia, bloody sputum and cheesy pneumonia. In chronic cases: respiratory insufficiency due to increased fibrosis, amyloidosis, and caverns carcinoma. Miliary tuberculosis: hematogenic generalization in a poor immunological state.

Symptoms of the musculoskeletal system:

Arthritis, tuberculosis of the spine (Pott disease), psoas abscess, osteomyelitis, and tuberculous dactylitis (also known as spina ventosa).

Further organ manifestations:

Tuberculosis may spread hematogenously in any organ and cause, e.g., pericarditis, meningitis, or ileus.

Diagnosis of Urogenital Tuberculosis

Tuberculin skin test (Mantoux test):

Intradermal injection of proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Depending on the immune status and history of tuberculosis, an active infection results in a more or less large papule with erythema within 72 hours. With competent immune status and without risk factors for tuberculosis, only an induration of more than 15 mm is suspicious for active tuberculosis. In patients with immunodeficiency or with present risk factors for tuberculosis, even smaller papels of 5–10 mm diameter speak in favor of active tuberculosis.

Interferon-gamma release assays:

The cellular immune system of a blood sample is incubated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens in vitro. If the patient already had contact with Tbc bacteria, more interferon-γ is released in the blood sample and detected by ELISA. The interferon-gamma release assay is particularly useful in patients with prior BCG vaccination.

Urine sediment and urine culture:

Urine sediment shows leukocyturia; sometimes, acid-fast bacteria might be detected after special staining. Urine culture is typically sterile. However, bacteriuria does not rule out tuberculosis.

Urine culture for tuberculosis:

The morning urine is sent for tuberculosis culture within special culture media on three consecutive days. The results (including resistance tests) will take at least four weeks.

Tuberculosis diagnosis with PCR:

PCR testing with morning urine enables fast detection of mycobacterium tuberculosis; resistance testing is impossible. The PCR has a higher diagnostic sensitivity than the urine culture; however, there is a higher risk of false-positive results.

Sputum Tests:

Sputum should be tested in suspected urogenital tuberculosis, even without pulmonary symptoms. Sputum is examined with microscopy, PCR and sent for culture.

Sonography:

Renal ultrasound can detect renal calcifications, dilatation of the calyces, hydronephrosis, renal abscess and renal atrophy. Involvement of the epididymis shows a mixed echogenic epididymal enlargement on scrotal ultrasound; a testicular manifestation is usually delineated as a hypoechoic mass.

CT:

CT scanning is the imaging method of choice for suspected urogenital tuberculosis. Signs of urogenital tuberculosis are urogenital calcifications, deformation of the pyelocalyceal system, renal caverns, hydronephrosis, scaring of the renal parenchyma, ureteral stricture, and bladder wall thickening.

|

Intravenous urography:

Plain films reveal calcifications of the urogenital tract. The excretion of contrast media may be delayed. Signs of urogenital tuberculosis are the deformation of the pyelocalyceal system, hydrocalycosis, renal caverns, pyelocalycial stenosis, ureteral stricture, and hydronephrosis [fig. urogenital tuberculosis in IVU].

|

X-ray of the chest and spine:

Signs of tuberculosis in the lungs or bone involvement also speak in favor of urogenital tuberculosis.

Retrograde pyelography:

Retrograde pyelography is done for diagnosis and treatment (internal stenting) of a ureteral stricture if hydronephrosis or renal failure is present.

Renal scintigraphy:

Renal scintigraphy determines renal function and clarifies the extent of hydronephrosis in patients with renal manifestation.

Notifiable disease:

Tuberculosis is a notifiable disease in many states around the world.

Treatment of Urogenital Tuberculosis

Standard treatment of tuberculosis:

Standard antituberculostatic treatment consists of isoniazid + rifampicin + pyrazinamide + ethambutol for two months. After resistance tests from urine culture are available, treatment is continued with isoniazid and rifampicin for at least four months, possibly with a different combination depending on the outcome of the urine culture. The duration of treatment for uncomplicated pulmonary or urogenital tuberculosis is six months. Before stopping medical therapy, an objective improvement should be seen (negative urine culture, remission in the imaging). See also section pharmacology, side effects and dosages of antituberculous drugs.

Monitoring during tuberculostatic therapy:

A complete laboratory test including blood count, liver and kidney function parameters, and uric acid is done before treatment and after 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks in patients without relevant side effects. An ophthalmologist should monitor therapy with ethambutol. Treatment with streptomycin harbors the risk of irreversible hearing disorders and tinnitus; ENT checks are necessary. Pyridoxine (vitamin B complex) is given to prevent neurological side effects, and allopurinol to prevent symptomatic hyperuricemia.

Resistance to standard drug therapy:

The medication is changed accordingly after receiving the test; the duration of the new drug therapy depends on the success of the treatment and is usually significantly longer than six months. Repeat urine cultures during therapy.

Quarantine:

Cooperative patients with only urogenital manifestation need not be isolated; however, a separate bathroom and toilet are recommended until the pathogen can no longer be detected in the urine. Protective measures such as a protective gown, face mask, and gloves are necessary when manipulating secretions that contain pathogens. For patients with infectious pulmonary tuberculosis, isolation in a single room, a gown, face mask, and gloves are required for nursing staff and visitors until the pathogen can no longer be detected in the sputum.

Follow-up after medical tuberculosis treatment:

After completion of drug therapy, urine cultures for tuberculosis are done every three months over a year.

Treatment of Hydronephrosis:

If sufficient renal function is present, internal stenting (DJ) or percutaneous nephrostomy is done (Shin et al., 2002).

Surgical Treatment for Urogenital Tuberculosis:

Before any surgical interventions, an anti-tuberculosis treatment for at least six weeks should be sought.

Nephrectomy:

A nephrectomy must be done for a nonfunctional kidney with tuberculosis. A partial nephrectomy is rarely indicated due to the efficiency of modern medical tuberculostatic treatment.

Treatment of Renal Abscess:

Percutaneous drainage or nephrectomy, depending on the extent of renal manifestation and kidney function.

Correction of ureteral strictures:

Internal stenting is necessary for the first six months of drug therapy. Surgical correction of ureteral stricture is indicated after persistent hydronephrosis with good renal function after drug treatment: endoscopic laser ureterotomy via ureteroscopy, open pyeloplasty, end-to-end ureteral anastomosis, ureteral reimplantation (with psoas hitch) or ileal replacement of the ureter.

Epididymectomy:

Epididymectomy is necessary in refractory epididymitis.

Bladder Augmentation:

Augmentation for a contracted bladder after medical treatment of tuberculosis is rarely necessary. If the distal ureters or the trigonum of the bladder were infected, cystectomy and a continent orthotopic urinary diversion might be considered.

| Urosepsis | Index | Malacoplakia |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Bergstermann und Häußlinger 2002 BERGSTERMANN, H. ; HäUßLINGER, K.: Tuberkulose.In: Internist

43 (2002), S. 861–871

Lenk und Schroeder 2001 LENK, S. ; SCHROEDER,

J.:

Genitourinary tuberculosis.

In: Curr Opin Urol

11 (2001), Nr. 1, S. 93–8.

Petersen u.a. 1993 PETERSEN, L. ; MOMMSEN,

S. ; PALLISGAARD, G.:

Male genitourinary tuberculosis. Report of 12 cases and review of the

literature.

In: Scand J Urol Nephrol

27 (1993), Nr. 3, S. 425–8. -

Shin, K. Y.; Park, H. J.; Lee, J. J.; Park, H. Y.; Woo,

Y. N. & Lee, T. Y.

Role of early endourologic management of

tuberculous ureteral strictures

J Endourol, 2002, 16,

755-8.

Wise und Marella 2003 WISE, G. J. ; MARELLA,

V. K.:

Genitourinary manifestations of tuberculosis.

In: Urol Clin North Am

30 (2003), Nr. 1, S. 111–21. -

Deutsche Version: Urogenitaltuberkulose

Deutsche Version: Urogenitaltuberkulose